There's a problem running through strength-training writing these days. Even good, informative articles struggle with it, perhaps including my own. Simply put, many writers seem to assume that the reader's number-one priority and goal in life is lifting. Like jobs don't exist, people don't have families, and we all spend the vast majority of our time either in the gym, prepping food, or on a foam roller.

These presumptions are understandable. When the author is a trainer or strength coach, they're going to speak with the perspective of someone who hangs out in a training facility all day.

But what if you sit at a desk all day? You still want to move some heavy barbells in your free time, either before work, at lunch, or after you clock out. And you want to do it without jacking yourself up.

This article is for all of you who want to make a program work within the storm that is life.

Rule 1: Pick a Program That Matches Your Life

This may sound like it's a copout or a way to exempt yourself from putting in hard work and staying consistent, but don't believe that for a second. If anything, you'll end up doing more high-quality training if you listen to me.

See, the only way you'll achieve results is if you put in the time and effort on a regular basis. That means you need to be able to actually follow the program! Even the best protocol will be ineffective if you only do two-thirds of the work each week due to a tight schedule, or if your workouts are awful because you lack energy.

Seven-day splits or two-a-days when you're a family man with a 60-hour-a-week job? Leave that for someone else. Otherwise, you'll end up down on yourself for missing workouts week after week, and give up on your program entirely.

It may not sound sexy, but start conservative and aim for progress. Cutting back to four or even three weekly workouts can do wonders for you if it means you'll show up feeling rested and ready to give a decent effort. Plus, that frequency gives you a safety cushion for the unforeseen.

Rule 2: Remember You're Not an Athlete

I didn't say you're not athletic. There's a difference.

Committing to advanced lifting protocols stops being a good idea when those programs are three steps ahead of where you're at physically. If your base-level strength training and conditioning aren't where they need to be, and you're not addressing the havoc that sitting at a desk is wreaking on your body, then your dalliance with the Smolov Squat Program is a ticking time bomb.

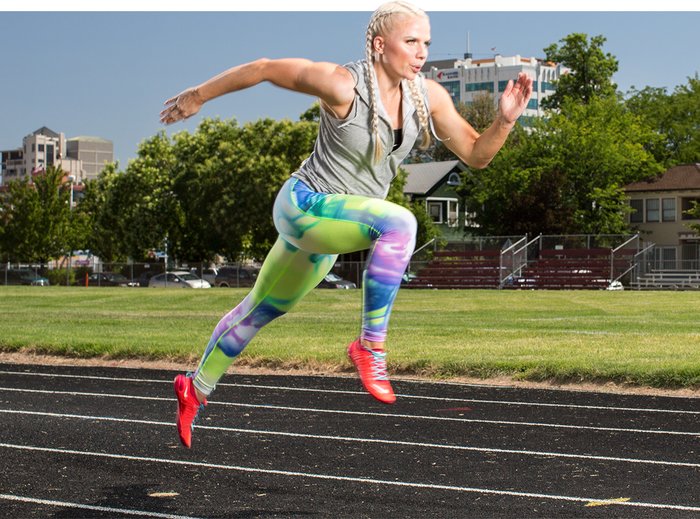

Most pro athletes have been doing very little other than playing and training for their chosen sport for years. The training methods they implement to help their performance shouldn't be shared by anyone other than athletes at their caliber. And to be clear, high-level powerlifters, CrossFitters, and bodybuilders are, for all intents and purposes, pro athletes.

Even ex-athletes—as a former university track athlete, I fall into this category, too—must sadly remember that those days are behind them. Sure, we may have more "muscle memory" going for us than the rest of the population, but training for life and function has to precede anything else.

It's a real wake-up call when you realize that stacking on the plates or pushing your work capacity to an all-time high may actually be doing you more harm than good. It behooves a lifter to recognize this sooner than later, and to build their program around these basic characteristics:

- It should help you get stronger.

- It should incorporate most if not all of the fundamental movement patterns: deadlifting, squatting, overhead pressing, overhead pulling, rowing, lunging.

- Full range of motion should be the norm in your resistance work and reinforced by mobility work.

- It should strengthen the posterior chain more than the anterior chain, with more pulling than pushing, and address posture as a noteworthy focus.

- It should always be focused on form first, and load second.

Rule 3: Remember That Progress Comes in Many Forms

This may be the most important point of all. Many lifters, coaches, and programs look at progression in the most absolute terms; namely, the ability to perform an exercise using more weight than you used before. While there's nothing wrong with this, a lifter who's not competing should look at things from a broader perspective.

Remember, age is a variable just like anything else, so maintaining a current PR as you age is a form of progress. Think about who's more impressive: a 30-year-old with a 500-pound deadlift, or a lifter like Charles Staley, who can pull that weight at age 55 while also staying in great overall shape?

You'll serve your body, health, and mind much better if you tweak these variables first before adding weight to a big lift:

- Increase the range of motion.

- Decrease the rest interval between sets.

- Slow the eccentric (negative) tempo.

- Pause at the top and bottom of each rep.

Each of these will help you truly own weights at various percentages rather than simply fretting over the big percentage. Making lighter weights feel heavy can also keep you from getting injured.

Rule 4: Don't Skip the Light Stuff

Push-ups, Turkish get-ups, planks, inverted rows, unweighted squats, goblet squats, lunges with torso rotation—what do they all share? Meatheads might look at these moves and see nothing that will help in the quest to get huge. But they're wrong.

It's a real shame when I see a 300-plus bench presser who struggles to control his body weight enough to do a set of 15 technically sound push-ups. Once someone's been under the bar—and pretty much no place else—for too long, dysfunctions can become as big a problem as they are for someone who hasn't trained a day in his life. That's not a comparison any experienced lifter wants to hear, but it's the truth.

Taking things back down to body weight, or something really close, and starting from scratch is the best way to refine your technique and reassess your levels of mobility. It's essential for an office worker to stay strong in these staples, because they help correct the imbalances caused by being chained to a desk for much of the day.

No, this doesn't mean you need to spend half of your workout hanging out on a foam roller. Here's one of my go-to routines, which takes me 10 minutes but gets me seriously ready to work. I don't always perform it in its entirety, but I pick and choose from these moves for at least 5 minutes. These can be done nearly anywhere—even at work or home.

- Bodyweight squat hold (heels elevated or flat)

- Squat with upward reach from the bottom

- Overhead squat with stick (heels elevated)

- Snatch-grip press from bottom of squat (heels elevated)

- Shoulder dislocate with band or stick

- Lunge hold with torso rotation and reach (both sides)

- Upper-back extension on foam roller

- Side-lying thoracic rotation (top leg on medicine ball)

Yes, You Can Still Train Hard

Our bodies were made to move, and you should be able to bust ass until you're lying on your back in a puddle of your own sweat. You just can't do it every day, and you need to respect that ritual by preparing for it correctly.

Aspiring to lift the most, train the hardest, or be the biggest when your lifestyle isn't on board will catch up to you. Give your body what it needs first. That'll allow you to make it do what you want, as well.