Despite all the jokes about International Chest Day being the sacred centerpiece of a lifter's week, the session itself is usually pretty uninteresting. Barbell or dumbbell bench, incline, decline, fly, cable cross. Maybe a couple of machines to more or less mimic a few of those same moves. Rinse and repeat.

You have more options! And what's more, you can find them on the same equipment you're using now. Use these moves and protocols to wake up that upper body and rediscover the good hurt!

1. Both stretch chest presses and partials

A well-traveled piece of gym advice is that you shouldn't allow your arms to go any lower than parallel to the floor when performing the dumbbell chest press. Sure, if you always lift the heaviest weight possible, then going any lower will feel like a battle for your life. But if you only focus on parallel and above, you'll miss out on muscle growth!

Stretching your muscles (i.e., eccentric training) is one of the most effective ways to stimulate gains in muscle size.[1] No, this doesn't mean you have to go so far down that you basically do a fly at the bottom. Instead, using a relatively light weight you can control, go to just below parallel, and stop as soon as you feel a stretch in your chest.

Once you've done, say, 3 sets that really hit that bottom position, it's time to pay some attention to the top. Why do both? Chest presses, like squats, are most difficult at the bottom of the range of motion, where the lever arm is the longest. As you get closer to the top, the lever arm shortens and you gain a mechanical advantage on the weight.

Translation: That relatively light weight you used in the full-ROM chest presses? Yeah, even though it was great for the weakest part of the movement, it's too light to create sufficient muscular overload in the less difficult ranges of motion.

With this in mind, a recent study compared the results from a group that trained with only 6 sets of full-range-of-motion squats to a group that did 3 sets of full-ROM, and 3 sets of heavy partials focusing on the top-half ROM. Both groups trained twice per week.[2]

At the conclusion of the seven-week study, although both groups improved in their squat strength, the group that did the combination of full- and partial-range-of-motion reps saw superior results.

Do your full-ROM reps like you're eating your vegetables, then up the weight and hit those partials like they're the sundae bar. And expect to feel them in both your chest and triceps afterward!

2. Three-way cable cross-over

One of the great things about cables is that relatively minor technique changes, such as where you stand in relation to the pulley, can create big differences in what's known as the "point of maximal loading," which is the point where the movement is most difficult. This can help you easily introduce variety into your training.

If you've only performed cable flyes standing in front of the cable stack, well, you're not alone. But you can also perform this movement standing either directly between or even slightly behind the cables, changing the nature of the movement and giving your chest a different stimulus.

It's worth noting, however, that the range of motion is usually smaller when performing flyes standing behind the stacks. You definitely won't feel the stretch the same way! So while you may end your other flyes with your hands meeting in something like a "most muscular" pose, I would recommend crossing them slightly in this variation and alternating the hand position with each rep.

Really focus on that squeeze at peak contraction! In fact, you could even pause at that peak contraction for 8 seconds at the end of each set, like I recommend in my video, "The Gritty Workout Your Upper Body Needs."

3. Single-arm cable fly

Now this is tough. But as an upside, you don't need to take over the entire cable cross station to do them. Any stack will do! So if your chest day is largely spent waiting around for other people to get off the equipment you need, try these.

In fact, you can perform a single-arm version of each of the three cable cross variations above. This helps you ensure left/right muscle balance, but it also brings in some serious activation from the core muscles in order to keep your torso stable. Just know that you'll have to start light!

4. Arrow-angle pause-go push-up

I'm a stickler about push-up form. The reason is simple: Plenty of people write off push-ups as being "too easy," but when I see them do a few reps, it becomes clear that they're simply performing the easiest variation!

Here's how I like to perform push-ups (as well as dumbbell presses): At the bottom of each rep, your arms should near to a 45-degree angle in relation to your torso, rather than the all-too-common 90-degree angle. So from the top view, your arms will form the shape of an arrow instead of a "T" with your torso.

What's wrong with the T-shape? For one, it requires less muscle activation in both the pecs and the triceps.[3] Plus, in the "T" position, healthy shoulder movement is limited, so you're getting more risk and less reward from the range of motion you have!

Once your form is correct, try this to make your push-ups more difficult: Pause for 8-10 seconds in the bottom position, with your chest just above the floor. Then, perform 8-10 normal reps. This type of "pause-go" set, as I describe in my article "4 Ways to Boost Time Under Tension," will give you a new respect for the simple push-up.

5. Contrast press sets

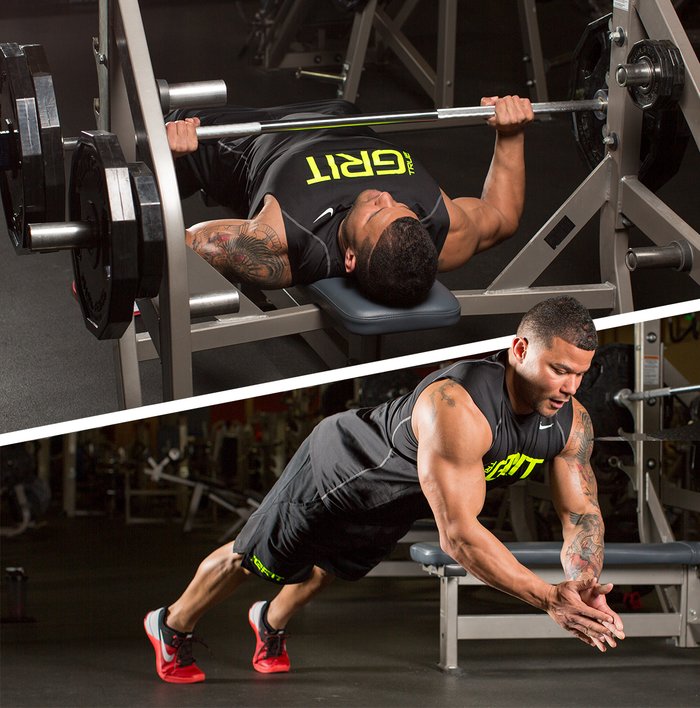

Contrast training is easy to explain: Start with a set of heavy lifts, like 3-5 reps, and follow it immediately with an unloaded explosive exercise using the same movement pattern and roughly the same number of reps.

Here's a perfect pairing to start you off: heavy bench press followed by clap push-ups. Just rack that weight, get on the floor, and then push yourself off of it!

This isn't just for fun. It might actually make you stronger! Contrast training creates an effect known as post-activation potentiation, or PAP, in which a muscle's explosive capability is enhanced when it is forced to perform maximal or near-maximal contractions.[4]

6. Triple-threat push-up finisher

This protocol involves doing a mechanical dropset, which starts with the most difficult push-up variation and progressively "works down" to the easiest version. So as you fatigue, the exercises become easier, allowing you to continue to crank out high-quality reps with less risk of injury.

Perform the following three types of push-ups, back-to-back:

- Push-ups with your feet elevated on top of a bench

- Regular push-ups from the floor

- Push-ups with your hands elevated on top of a bench

Go for max reps on each variation, and rest up to 15 seconds in transition between push-up variations. One time through the protocol should be enough.

Don't let the fact that this protocol involves low loads for high reps fool you into thinking it's somehow less effective at building muscle than heavy sets. Research shows that maximizing time under tension by lifting a lower load to or near failure produces hypertrophy (gain in muscle size) similar to that produced by lifting a heavy load to the same point.[5]

But to get those benefits, you need to make each of the three steps matter. Make this finisher live up to its name!

References

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857-2872.

- Bazyler, C. D., Sato, K., Wassinger, C. A., Lamont, H. S., & Stone, M. H. (2014). The efficacy of incorporating partial squats in maximal strength training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 28(11), 3024-3032.

- Contreras, B., Schoenfeld, B., Mike, J., Tiryaki-Sonmez, G., Cronin, J., & Vaino, E. (2012). The Biomechanics of the Push-up: Implications for resistance training programs. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(5), 41-46.

- Horwath, R., and Kravitz, L. (2008) Post activation potentiation: A brief review. IDEA Fitness Journal, 5(5), 21-23.

- Mitchell, C. J., Churchward-Venne, T. A., West, D. W., Burd, N. A., Breen, L., Baker, S. K., & Phillips, S. M. (2012). Resistance exercise load does not determine training-mediated hypertrophic gains in young men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(1), 71-77.