As a young man, Mark Twight was convinced that his life would end at age 26. It was an arbitrary number, he admits today, but as a world-class mountain climber, he had plenty of time shivering in tents and clinging to exposed rockfaces to imagine doom lurking just over the horizon. Waiting at home for this death to find him wasn't Twight's style, though. Instead, he built his reputation by targeting routes which other climbers deemed impossible or suicidal, and he conquered them quickly with minimal equipment.

"I am willing to cut it all away in order to have my way, to live how I want, and for only as long as I want," he writes in his memoir Kiss or Kill: Confessions of a Serial Climber. "I made life or death decisions like I was choosing between brands of beer."

But then, something happened—or didn't happen. "Strangely, I survived 20 years after my predicted expiration date," Twight writes on the website for Gym Jones, a training center he and his wife founded after he retired from climbing in 2000. But make no mistake: The intensity that defined his climbing career came down from the hills with him.

After starting off training military units in high-altitude settings, Twight has carved out a niche helping professional fighters, football players, endurance athletes, and A-list actors achieve their full physical potential. He trained the Spartan fighters in director Zack Snyder's 300 and the forthcoming sequel 300: Rise of an Empire, as well as the stars of Snyder's new Superman reboot Man of Steel.

In exchange for extreme results, he is known for demanding total physical and psychological commitment from his clients—fitting, when his gym's name is a play on Jim Jones, the cult leader who convinced hundreds of his followers to commit suicide in 1978. Fresh off the release of Man of Steel, Twight spoke with Bodybuilding.com about the challenges of getting inside actors' minds and transforming stars like Henry Cavill and Russell Crowe.

I like to think we were the first generation of climbers who were training using "artificial" means. A lot of those guys back in the old days, maybe they'd go running, but a lot of others were just kicking Hacky Sacks and smoking dope. That didn't apply to what we wanted to do.

We found our own way in the beginning, and then somewhere in the mid-90s, around '94 or '95, I started working with a guy named Steve Ilg, who wrote The Outdoor Athlete. His outdoor fitness business was a nice marriage of internal and exterior principles for physical and psychological training. He steered me in a good direction, and then I started working with a protégé of a Russian guy named Ben Tabachnik, a strength coach in the ex-USSR who came over here and worked with a lot of professional sports teams. He's a brilliant guy.

I retired from climbing in 2000 and sort of cast around for something to fill the void—because that was 20 years of my life spent doing that, and only that. I went through various phases, and in November 2003, somebody introduced me to CrossFit. I fell for that shit hook, line, and sinker, and spent a bunch of time involved in that project.

.jpg)

Then I realized, right about when [my wife Lisa and I] started training on our own in our own space, that as a means, it wasn't fulfilling the needs that we had. We also couldn't stomach the bullshit politics coming down from the top of that organization anymore, and we realized that despite this idea that there's a sort of one-size-fits-all type of training, we didn't see it [as ideal] for our objectives.

So we decided to go down the road of more individualized training. We started training military in 1999, mostly cold-weather high-altitude training, and that continues to this day. As our gym evolved, we also developed more of a group orientation, and educated people in our certified military seminars so they could direct their training on their own. And then at some point, another path developed that was more individual, where everybody has a different history, expectations, and demands for work or sport.

Our main training philosophy is simple. It all comes down to: "Find the problem, fix the problem." We train a bunch of endurance athletes, and we've got a bunch of NFL players who work with us in the offseason. And those are two different problems.

In a movie context, obviously the training and dietary program for the original 300 was completely different than it was for Man of Steel. In one job we were uncovering what was there, but part of the Man of Steel job was to put more there. Working with Henry [Cavill] was completely unique, because his condition had to be held for six months from the start of shooting. I think it was a 122-day shoot, and so he had to look the same on February 3, which is the last day of shooting, as he did on August 1.

Peaking someone for one, two, or three days, like for a contest, a shirtless scene, or a particular athletic event, is actually easy, but to get someone there and hold them there for six months? Every person who does any type of physical training knows how hard it is to maintain their condition along a timeline.

Mark Twight Talks About Training Henry Cavill

Watch The Video - 02:24

On the movie project, we have control of the diet, because if we don't, then the training doesn't matter. It's that simple. If a guy is training with us in the gym five times a week for 2 hours, that leaves 158 hours for him to fuck everything up if left to his own devices.

As far as the supplementation goes, I'm not a big believer. In terms of what we had Henry use, it all came down to a basic multivitamin, a lot of essential fatty acids—he was going through the Udo's Oil in liter volume—a probiotic to help digest that fat intake that he had, and magnesium. The magnesium, a product called Calm, he would drink at night to coast into sleep.

But that's it. I know a lot of people believe in a pre-workout formula, but if we're asking a guy to sleep 9-10 hours per night, then stimulants that keep him hopped up for 8 hours aren't the way.

That being said, during the phase where we were putting weight on him, the caloric intake was excessive [laughs]. That meant we used protein powder in his post-workout shake, but the main caloric density was from coconut milk, heavy cream, yogurt, fruit, and stuff like that.

When we supply meals for trainees in this context, we work closely with different providers in the different locations we're in. We find someone who uses food from organic sources, who understands working with athletes, and with whom we tune the macronutrient profile and the caloric intake.

Basically, I was with Henry for 11 months, had a month off, and then rolled right into 300: Rise of an Empire, which was another 6 months. These were different situations, working with different individuals, different objectives, and different processes of psychological management in order to get someone to work as hard as is necessary.

I need someone to pay attention 24/7. I have to teach them to be honest with us, so that we can fine-tune on a daily basis what needs to be done according to the stress from work that's going on, the fact that they live in a hotel, and that once shooting starts guys work 12-16 hour days. We have to fit the training into that while also dealing with the guy who needs to blow off steam and says, "Hey, I'm going to go drink a bottle of vodka tonight." I'm like, "OK, well, we'll train tomorrow at 2."

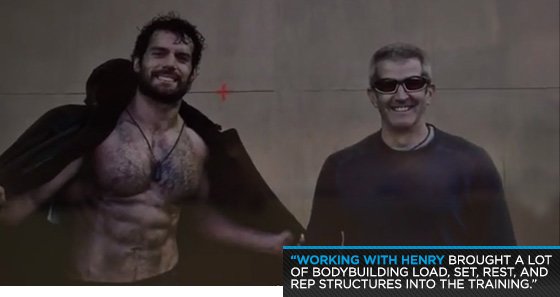

There's a whole educational process that goes with it. And the more we do it, the more it trickles back to what we do in our gym. Working with Henry brought a lot of bodybuilding load, set, rest, and rep structures into the training, especially during the bulking period, because that's what was needed.

The whole hypertrophy thing doesn't come into it for a lot of our clients who train for sport-specific outcome. It's only when someone needs to put on weight to move up in a weight class as a fighter, or when we worked with [San Francisco 49ers wide receiver] Chad Hall. The NFL wouldn't look at him because he's 5-foot-8, and after he graduated from the [Air Force] Academy, he had gotten down to 175 pounds. So we had to put 18 pounds of weight on him so he could actually get a look at a pro day and get signed to a team.

But ultimately, all of the projects we do inform all of the other projects. They can't be separated, especially because bias as a trainer is something that trickles down to everyone. For instance Rob, our general manager and the training director of the gym, loves to deadlift and overhead squat. Well, we went through a period where everyone else in the gym apparently loved to deadlift and overhead squat as well. That's kind of a hard thing to break out of.

If we do a lot of these 5-3-2 cluster sets, or 10 sets of 10, or 4 sets of 15, 4 sets of 4 with Henry, it's really hard to totally switch gears and not have that have an effect on other people. But as long as we're aware of how some projects influence other projects and training, I don't think it's a bad thing at all.

One of the things I invariably say to someone when they say, "Wow, he was huge" or, "He got so strong," is that the biggest changes he went through weren't physical. Yes, he became physically incredible. I mean, some of the numbers he put up, especially for a guy whose full-time job is being in front of the camera, were shocking. But because he physically overcame these incredible challenges, and he changed his body composition of his own will, it changed Henry's attitude and his bearing.

Henry Cavill Trains with Mark Twight

Watch The Video - 02:40

Point number one in our training philosophy—and this applies to everyone—is that the mind is primary. Because all of this stuff, the actual physical effort and transformative process, originates in the mind. So we spend a lot of time talking, and every training session begins with an interview. And we have to adjust training and diet to adapt everything else. Training doesn't exist alone, and it's not the most important thing. It's an integrated part.

So there's a lot of discussion and a lot of sharing. Depending on a person's level of confidence, if we have a really hard training week, some workouts might be two-hour discussions—"You're not doing anything today, we're going to have a chat." One of the reasons that we're effective at this, and one reason that actors and actresses who train with us continue their training afterward, is because of the psychological involvement we have.

A year after we wrapped on Man of Steel, I went back out to L.A. to get Henry ready for a commercial. It was remarkable what he had maintained just using his own self-discipline, as well as the basic tools we were able to teach him during our time with him.

It's important to train with them. But when it comes to the seriously heavy lifting, it's always good if the trainer can put a beat-down on the client. So Michael Blevins, who was my assistant on both Man of Steel and 300: Rise of an Empire, fulfills that "big guy" role. Henry's deadlift was considerably larger than mine, so I'd bring Michael in and say, "Here, show him how it's done."

But different clients will respond to different motivations. Some respond to the carrot, some need the stick, some need to be tricked, some are motivated by shame, and others need to be led from the front.

I get fit in a gym sense on these jobs, because I'm doing stuff with the clients a lot of times, and not just demonstrating. There was a memorable workout of back and front squats during the Man of Steel where Henry and Michael and I did 10 sets of 10, and the only rest we got was the amount of time it took for the other guys to do their sets.

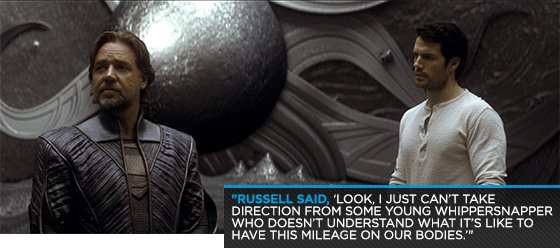

I also spent a lot of time on this job with Russell Crowe. He had just come off another movie where he had to put on a whole bunch of weight, so then we spent 5 or 6 weeks in Chicago, and then we went to Newfoundland with him, and Michael held down the fort with the other actors in the U.S. I had to be there all the time, because I have to take full advantage when someone's psyched to do something. If he wakes up at 5 in the morning and says, "I need to do something now because I don't have much time the rest of the day," well, that's what we're doing.

I reached him via the bike. Russell and I spent a lot of time on our bicycles, because he loves doing it. His body was also beaten up enough that he couldn't handle super high-intensity training, so we had to substitute duration. There were a couple of days where we went on these 60-mile rides. He was on a full downhill mountain bike, so 60 miles on dirt, gravel, and paved roads is not insignificant.

We're also a similar age, which helped a lot. Russell said, "Look, I just can't take direction from some young whippersnapper who doesn't understand what it's like to have this mileage on our bodies."

When all that happened around the original 300 workout, I was dismayed. I actually came across a line the other day where somebody said, "This is an incredible muscle-building workout." And I'm like: "Wait, it is 300 repetitions of something at sub-maximal weight. How could it possibly build muscle—unless you're coming off the couch, in which case you're not going to be able to do the workout in the first place?"

I'm going to steal a quote that Dan John laid on me the other day. He said "Most people just want a 20-minute workout and a bagel." We were standing in bagel shop at the time, which was kind of funny. But I think the reason someone would get fixated on a particular named workout is because the totality of what's required to achieve that kind of objective is too big to comprehend. So we have to take things and compartmentalize them.

Vincent Regan, the guy who dropped 40 pound in 8 weeks on the 300 job, trained six days per week. And he followed his diet. He wasn't eating more than 1,800 calories per day during that time. But that's the kind of thing where it's like, "Whoa, don't tell me that, because then I'm going to have to accept that the so-called 'secret' is hard work, discipline, and 24/7 awareness."

There's an honesty that's required when looking at these sorts of things. To look at it from an Olympic athlete point of view, you could say, "Oh, I got my hands on the last three months of training that Usain Bolt did prior to the Olympics. I'm going to do this!" Well, I'm like, "Yeah, but you're missing the lifetime that comes ahead of those three months. You're missing the three-and-a-half year workup that began after the last Olympics."

That's what this guy did, but I don't have the same time available and the same support system. It takes honesty when it comes to your self-assessment of your condition, and what you could possibly do right now. Then the path between those two things writes itself. It becomes really clear.

Somebody asked the other day, "Hey, can an ordinary guy on the street become the Man of Steel with your workout?" And I say no, because there's not a universal physical recipe. If it took 20 years to achieve your current condition, then maybe, if you dedicate all your extra time outside of work and family responsibilities, you could change your current physical condition in a meaningful way with 3 months of constant attention and hard effort. But to change the habits that you developed over those 20 years, and that caused the current condition that you're in? That's going to take years to overwrite.

Until those habits become automatic—until you're confronted by the doughnut tray at the office and you don't even notice that it exists anymore, and you don't have to go through this process of "Do I get the doughnut? Don't I get the doughnut?"—then you have to pay attention. There are 168 hours in a week. One hour three times per week in the gym is no counterbalance to all of the other behavior in those other 165 hours.