I have a saying: Sitting is death.

Sure, sitting causes muscle tightness, but that's not all. Long periods of sitting devour your potential for peak athletic performance. This is even truer for people who spend 7-9 hours per day sitting in compromised positions, in chairs designed primarily for aesthetics, not function. It's no wonder you feel like a broken-down mess and experience back, shoulder, and hip pain, and carpal tunnel agony after sitting in a plane, car, or at your work desk. You force yourself into a toxic position which feasts on athletic potential.

The trouble is, you can't avoid sitting. It's an unfortunate reality of modern society. So the question is: How do you avoid or at least reduce the havoc wreaked by extended sitting?

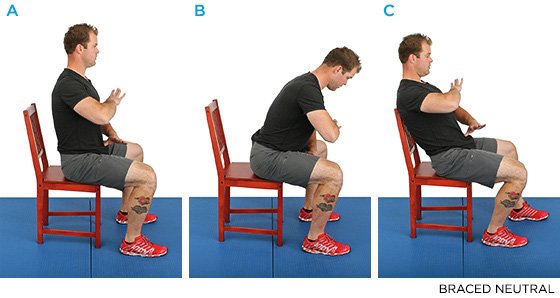

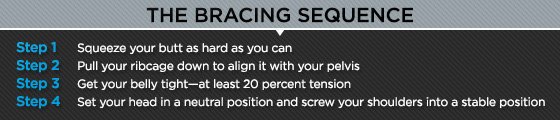

For starters, learn how to sit. Sitting—like standing—is one of the most technically challenging things we do. Yet most of us are clueless when it comes to sitting well. In order to stabilize your spine in a neutral position, you have to get organized while standing by following the bracing sequence. (Note: A basic understanding of how to box-squat also plays a key role in organizing yourself to sit.) Once seated, you need to keep at least 20 percent tension in your abs to maintain a rigid spine.

And herein lies the problem: Keeping your abs engaged at 20 percent is extremely taxing. All the research indicates that it's not muscular strength, but muscular endurance, that dictates loss of spinal position. (Muscular strength is like doing a 1-rep-max back squat, while muscular endurance is like doing a 30-rep back squat.) This is why so many people tweak their backs at the end of a run or workout.

This also helps explain why most people collapse into a horribly rounded or overextended position after only a couple of minutes. It's more comfortable and doesn't require any work. Maintaining a stable position, on the other hand, takes extreme focus and abdominal endurance.

The best way to avoid defaulting into a bad position is to stand up and get reorganized every 10-15 minutes. It's almost impossible to remain in a good position for anything longer than that. I know—this is a pain in the ass and not always possible. But if you want to heal your body and reach your performance goals, you have to do the work. You have to make sacrifices. So pony up!

Another helpful strategy is to change your position as often as possible. You have to remember that you don't need to stay locked in a sitting position all the time. You can kneel in front of the computer to open up your hips while answering emails, go for a walk while talking on the phone, or even stretch while sitting at your desk. The key is to avoid correcting your posture once you're already seated.

The moment you sit, your glutes go on vacation. This not only places additional stress on your spine, but also makes it difficult to stabilize your pelvis in a neutral position. So if you fail to address the bracing sequence before you sit down, don't keep your belly tight, or round or overextend your spine once seated, fixing your position from your chair is difficult. For example, say you flop down into your favorite armchair for Super Bowl Sunday and slouch.

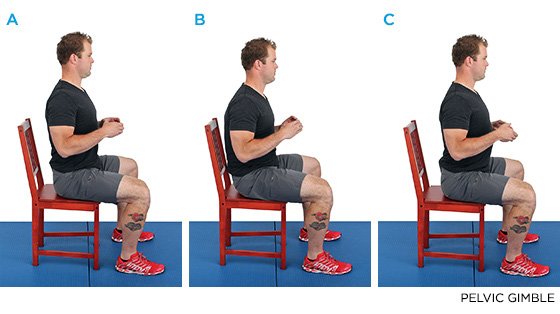

After the pre-game, you become aware of how bad your posture is (or just become uncomfortable) and try to fix it by flattening your back. Although it may seem as if you're rectifying the problem, all you're doing is going from a flexed position to an overextended one. The same thing happens during a squat when athletes fail to brace from the top position. It's a big thumbs down.

Pelvic Gimble Tip: If you find that you round forward and try to correct that by straightening your back, you'll probably just end up in an overextended position. Instead, stand up, run through the bracing sequence, and then sit back down, keeping your back flat and belly tight.

In addition to getting up and changing your position, work on restoring function to the tissues that become adaptively short and tight after long periods of sitting. As a rule, you should mobilize for four minutes for every 30 minutes of sitting.

For example, you could do the couch stretch—a brutal hip opener—for two minutes on each side every half hour. The idea is to tackle the areas that become restricted, specifically your glutes, psoas and other hip flexors, thoracic spine, hamstrings, and quads (to mention a few). Think of it as a mobilization penalty based on sitting time.

Episode 2: Don't Go In the Pain Cave

Watch The Video - 04:40

Note: Couch Stretch tutorial begins at around 2:20.

These are just ideas to get you thinking. It doesn't matter how much you mobilize, stand up, or change your position, or what kind of chair, keyboard, or mouse you have: if you hang out in a position that compromises your posture, you will continue to experience the same consequences.

That said, getting an ergonomic chair or using some kind of lumbar support (which is particularly useful during long car rides) gives your lower back a break and puts you into a more protective posture.

Your abs should have some tone all the time. The minimum tension to maintain a braced-neutral spine for basic standing and sitting positions is about 20 percent of your peak stiffness. However, the moment you add dynamic movement or axial load (a force compressing on your spine), you need to increase abdominal tension or trunk stiffness to avoid rounding or flexing your back.

For example, if you run around the block or do push-ups, you might need about 40 percent trunk stiffness to maintain a good spinal position. But if you go for a max deadlift, you will need 100 percent abdominal tension.

Perhaps you can't relate to numbers like 20 percent or 40 percent. You might find it helpful to rate abdominal tension on a scale from 1 to 10—with 1 being little to no tension, 10 being max tension. On this scale:

- Sitting in a chair requires a 2 (20 percent).

- Push-ups or running around the block requires a 4 (40 percent).

- Max back squat, deadlift, or a 50-meter sprint requires a full 10 (100 percent).

In short, the tension necessary to maintain a braced, well-organized spine largely depends on the action and load on your spine. You need to understand how and when to cycle up to peak stiffness based on the demands of your exercise or activity.

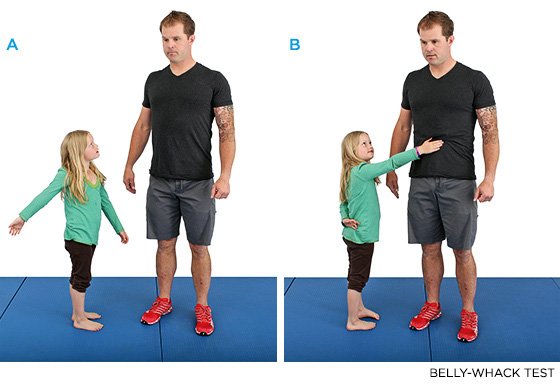

The belly-whack test is another way to help bring consciousness to a braced-neutral position and the 20 percent constant-tension concept. It's simple: You should always have enough abdominal tone to take a whack to the belly. We do this at our gym and around the house. If you have a spongy middle, you get caught right away.

A cobra doesn't cruise around with its head up and hood flared all the time: It hits peak tension when it gets ready to strike. Similarly, you don't want to walk around with trunk stiffness at a 10 or attempt a high rep, heavy back squat with abdominal tension at a 2.

Knowing how much tension you need to preserve a braced-neutral position is a skill that requires practice. The better you are at this, the less energy and thought you have to put in to managing abdominal tension. It becomes instinctual.

Braced Neutral Tip: You're not limited to just sitting perfectly upright: You can still lean forward, or lean back, while maintaining a braced-neutral spine.