As a nutritionist, I find it fascinating how nutrients change their function across nature. A molecule can serve a specific role in the plant in which it is made, yet serve an entirely different physiological purpose when ingested by a human.

Similarly, while there are countless plants and fruits which offer limited or no benefit to us, others only seem to get more valuable and promising, from root to stem, the more we study them. Cacao is one that falls in the latter category, as I discussed in a previous article. Another is the pomegranate.

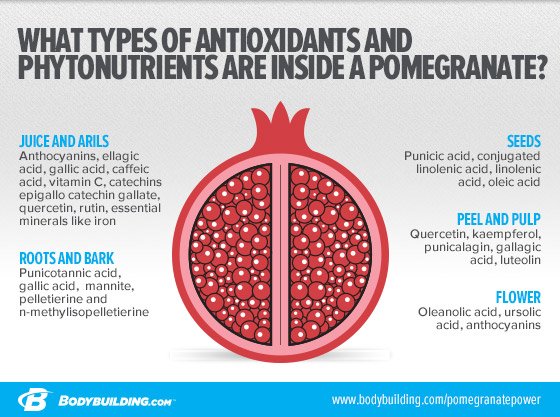

Most people know by now that the pomegranate fruit provides some vitamins, essential minerals, and a rich assortment of antioxidants.

Barring that, you might be familiar with its unique and delicious flavor in juice blends, martinis, and margaritas. (Or, maybe you're somewhere in the middle, and you ordered a cocktail containing pomegranate because it was "healthier.")

However, aside from its more general health and culinary benefits, it also offers distinct performance benefits to athletes and fitness enthusiasts including weightlifters and bodybuilders, CrossFit competitors, and runners and other endurance athletes.

Looking at this brightly colored, labor-intensive fruit on your kitchen counter, it can be hard to imagine what a nutritional go-getter it is. But the secret is out! Let's peel back the skin of this long-revered superfood and see what it can do for you.

The Mystical Fruit

The pomegranate's relationship with human civilization goes back as far as recorded history, and extends deeply into the realms of legend and religion. It was mentioned in Mesopotamian clay tablets nearly 5,000 years ago, and had a strong symbolic presence in nearly every society around the Mediterranean, as well as ancient China, India, and the Middle East. It is mentioned in the Old Testament, the Quran, and is often seen accompanying the baby Jesus in a variety Christian artwork. Of course its precise function varied in each tradition, but they all agree that this fruit was powerful, sacred stuff.1

Even the pomegranate's name is powerful. The first half of its Latin name, Punica granatum, was the Roman name for Carthage, the ancient capital of the Phoencian civilzation, where pomegranates grew in abundance.2 Meanwhile, the pomegranate is known by the French as grenade. If that word looks familiar, it's because French soldiers thought that grenades themselves looked a lot like pomegranates, and were similarly packed with power—hence the name of the weapon.

The anatomy of the pomegranate is a little complex, but what would you expect from such a potent fruit? On the outside, the pomegranate shrub has leaves, a flower, a stem or "crown," roots, and bark, all of which are consumed in some form (often as extracts) by humans for a perceived health benefit. But the edible fruit gets the most press, and rightly so.

The nutrient-dense outer skin or "husk" of the fruit is connected to a fibrous internal support network, the mesocarp, which contains pockets containing clusters of what are known as arils. These little sacks are the part of the pomegranate that you spend all that time digging around to find, and they contain the portions of the plant with the most clear-cut and research-supported benefits: the crunchy seeds and the tart juice.

Pomegranate has Potential!

Pomegranates have long been known as good sources of essential nutrients such as vitamin C, potassium, and iron. However, the tangy taste of the pomegranate and its juice suggests even more benefit. Both pomegranate skin and juice are rich in natural phenols, the acclaimed phytonutrients that are rich in many reputed superfoods such as berries, olive oil, green tea, cacao, coffee, nuts and spices, and various leafy vegetables.

In particular, pomegrantates are heavy with phenolic molecules such as ellagic acid and quercetin, as well as polyphenolic compounds such as tannins. These substances have been linked in some studies to decreased rates of cancer and heart disease, although they, like antioxidants in general, remain a rich area of future research. Much of the fruit's antioxidant capacity is derived from vitamin C and phenolic molecules, both of which seem to be in greater concentrations early in the ripening process.3

Pomegranates are also rich in nitrates, much like beet root and dark leafy green vegetables.4,5 Nitrates are simple nitrogen- and oxygen-endowed molecules, and were once considered to be nothing more than metabolic byproducts and even potentially hazardous components.

Today, however, both nitrates (NO3) and nitrites (NO2) are thought to contribute to blood vessel nitric oxide (NO) balance within tissue, and especially tissue with high oxygen demands, such as muscle.

When consumed regularly, pomegranate has been suggested to possess anti-atherosclerotic, anti-aging, and memory-supporting characteristics.6-8 Pomegranate juice consumption has also been linked to a reduction in systolic blood pressure, partly by helping to put the brakes on the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) system.9,10

Based on our current understanding, it appears that nitrates have a more acute impact on blood flow via nitrates, while other pomegranate nutrients such as catechins and polyphenolics support healthy daily blood flow by helping to regulate the ACE system.

Pomegranate Gets the Juices Flowing

For most of the last decade, arginine dominated the nitric oxide supplement marketplace. Over time, however, researchers have begun to recognize its limitations, such as the way the way it is rapidly broken down in the body by arginase, necessitating high doses to have a performance impact. Meanwhile, researchers have also been discovering the potential of vasoactive natural nutrients such as catechins, nitrates, nitrites from fruits and vegetables like pomegranates, which seem to be at least more efficient, and possibly more effective, than arginine in supporting circulation to muscle.

Here's how it works: During periods when we are simply hanging out, skeletal muscle might receive about 15-20 percent of the 5 or more liters of blood being pumped by the heart each minute, through tens of thousands of miles of blood vessels. However, during intense, ongoing exercise, the demands made by muscle increase dramatically. As much as 80 percent of blood flow surges into muscle tissue at this time, delivering oxygen and nutrients while picking up carbon dioxide and heat to be released by the lungs and skin.

Once ingested, nitrates from pomegranate and other foods are efficiently absorbed from the digestive tract and circulate in the bloodstream. While much of the nitrate is filtered out by the kidneys, some is taken up by the salivary glands. Nitrates are released from these glands into the mouth, where bacteria convert it to nitrite, which is then swallowed and absorbed.

During exercise, the muscles struggle to find enough blood and are, in a manner of speaking, suffocating. In this situation, excess nitrite can be converted to NO to support vasodilation (the widening of blood vessels) and boost blood flow, delivering more oxygen to muscle tissue. As you know if you take a pre-workout that contains vasodilation-supporting ingredients, this can result in an intense blood rush or "pump" to the muscle.

But studies have also indicated that nitrates and nitrites also have the potential to help the body use oxygen more efficiently, meaning that an athlete could use less oxygen in a given workout, or accomplish more work before getting exhausted.

Recover Your Strength Faster

The positive research about nitrate-endowed plants has been piling up in recent years, even though pomegranate-specific research in the sports realm is still somewhat limited. We can certainly learn a little about pomegranates from research into beet root extract, given the similarities in nitrate content between the two. Extrapolating from the health-focused pomegranate studies can provide other ideas. But recently, a few studies have zoomed in on pomegranate and its specific applications to athletes.

To see what pomegranate could do for lifters, researchers at the University of Texas gave men who routinely performed resistance training either 500 ml of pomegranate juice or a placebo for nine days.11 After five days, the participants then performed 3 sets of 20 reps of single-arm eccentric biceps exercises and 6 sets of 10 reps of single-leg eccentric leg extension exercises. The researchers then tracked rates of strength recovery. They found that, 2-3 days later, the subjects who took pomegranate extracts had recovered significantly more of their strength than those who took a placebo. Based on these results, it seems regular consumption of pomegranate juice could support recovery processes, potentially allowing for more training volume over time, and in turn better gains.

In a different study by the lab team, subjects performed similarly high-volume biceps and thigh workouts, with the goal of producing both exhaustion and delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS). Afterward, they either drank 250 ml (approximately 1 cup) of pomegranate juice twice daily or a placebo.12 Over the next seven days, the researchers assessed that strength recovery was better and soreness significantly less in the subjects' biceps when they consumed the pomegranate juice.

In a study that was just completed at the University of North Carolina, a standardized pomegranate extract was provided to runners 30 minutes before an intermittent sprinting challenge, and researchers compared it to the same trial on a different day using a placebo.13

The pomegranate juice increased blood flow after 30 minutes, which was immediately before they started running. At that time, the subjects also reported experiencing a nearly immediate positive impact on their feelings of vitality. Once the sprinting challenge began, subjects were able to run more intensely, run longer, and they experienced increased blood flow parameters 30 minutes after the challenge.

In a recent multi-ingredient pre-work study, pomegranate and beet root juice in addition to creatine, beta-alanine, BCAAs, and caffeine led to greater gains in muscle mass and strength and total body leanness after six weeks compared to a placebo.14

This matches a growing trend among pre-workout supplements to include fruit and plant extracts like pomegranate, beet root, tart cherry, and green tea both to boost blood flow and to support exercise recovery.

Crack One Open!

While the research is still young, pomegranate juice and extract seems at this time to have great potential as a performance supporting food and supplement.

Increased power production, oxygen efficiency, and blood flow are all performance benefits that could appeal to anyone engaged in prolonged exercise.

Reduced muscle soreness and faster strength returns post-workout are just the icing on the cake. In addition, studies indicate that the benefits could be both acute from supplementation, and chronic from drinking juice or extracts.15, 16

The downside, historically, is that pomegranates are expensive, time-consuming to prepare, and their juice will stain your clothes. But given the explosion of pomegranate products, from pre-seeded fruit containers to juices and extracts, those excuses don't stand up like they once did.

Open your mind to the pomegranate, because based on the current research, this looks to be a superfood that lives up to the billing!

References

- Viuda-Martos, M., Fernandez-Lopez J, and Perez-Alvarez JA. Pomegranate and its Many Functional Components as Related to Human Health: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010 nov; 9(6): 635-654.

- Jurenka JS. Therapeutic applications of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.): a review. Altern Med Rev. 2008 Jun;13(2):128-44.

- Wildman REC, Jalili T, Bruno R. Nutrition composition and antioxidant measure (ORAC) of unripe vs ripe pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice and pomace. Exp Biol, 2011 Apr, Washington DC.

- Hertzler S. Nitrate supplementation for cardiovascular health and exercise performance. SCAN's Pulse. 2012; 31(4): 7-11.

- Hord NG, Tang Y, Bryan NS. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jul; 90(1): 1-10.

- Stowe CB. The effects of pomegranate juice consumption on blood pressure and cardiovascular health. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011 May; 17(2): 113-5.

- Bookheimer SY, Renner BA, Ekstrom A, Li Z, Henning SM, Brown JA, Jones M, Moody T, Small GW. Pomegranate juice augments memory and FMRI activity in middle-aged and older adults with mild memory complaints. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. Epub 2013 Jul 22.

- Ghosh D, Scheepens A. Vascular action of polyphenols. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009 Mar; 53(3): 322-31.

- Aviram M, Dornfeld L. Pomegranate juice consumption inhibits serum angiotensin converting enzyme activity and reduces systolic blood pressure. Atherosclerosis. 2001 Sep; 158(1): 195-8.

- Basu A, Penugonda K. Pomegranate juice: a heart-healthy fruit juice. Nutr Rev. 2009 Jan; 67(1):49-56.

- Trombold JR, Barnes JN, Critchley L, Coyle EF. Ellagitannin consumption improves strength recovery 2-3 d after eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Mar; 42(3): 493-8.

- Trombold JR, Barnes JN, Critchley L, Coyle EF. Ellagitannin consumption improves strength recovery 2-3 d after eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Mar; 42(3): 493-8.

- Trexler ET, Melvin MN, Roelofs EJ, Wingfield HL, Smith-Ryan A. The effects of pomegranate extract on blood flow and running time to exhaustion. J Sci Med Sport. In press.

- Lowery RP, Joy JM, Dudeck JE, Oliveira de Souza E, McCleary SA, Wells S, Wildman R, Wilson JM. Effects of 8 weeks of Xpand 2X pre workout supplementation on skeletal muscle hypertrophy, lean body mass, and strength in resistance-trained males. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013 Oct 9; 10(1): 44.

- Wylie LJ, Kelly J, Bailey SJ, Blackwell JR, Skiba PF, Winyard PG, Jeukendrup AE, Vanhatalo A, Jones AM. Beetroot juice and exercise: pharmacodynamic and dose-response relationships. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013 Aug 1; 115(3): 325-36.

- Wilkerson DP, Hayward GM, Bailey SJ, Vanhatalo A, Blackwell JR, Jones AM. Influence of acute dietary nitrate supplementation on 50 mile time trial performance in well-trained cyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012 Dec; 112(12): 4127-34.