"Tony, how much weight should I use?"

I get this question a lot, particularly when I'm working with someone who has little experience in the weight room. And I'm not going to lie: Many times, when I hear the question, it's often like someone taking their fingernails and scraping them down a chalkboard, Freddy Krueger style.

On one hand, I can't blame a client for asking how much weight they should use. They're not seasoned veterans, and it's my job to be their guide on these sorts of questions. But on the other hand, I also know that the question of "how much" is one that people tend to overcomplicate more than almost any other.

In this situation, I occasionally offer up a simple but somewhat facetious answer like, "If your goal is to perform 8 reps and you can easily bang out 15, add some weight. Conversely, if you barely eek out 4 reps, the load is probably too heavy and you need to check your ego at the door."

But that's only a short-term answer, and it misses the greater point. When someone asks about weight, what they really ask is, "How can I choose weight in order to keep getting stronger today, tomorrow, and six weeks from now?"

As a strength coach, this sort of strategic planning is my bread and butter. If you're tired of guessing—and guessing wrong—then it's time to get serious about progressive overload.

Introducing Progressive Overload

Progressive overload is the gradual increase of stress placed on the body during training. The body is much smarter than we give it credit for and will adapt to most stresses placed on it.

To see consistent and long-term results in the gym, you must gradually increase the total amount of weight you move. I often see people use the same weight week-in and week-out, and they're left dumbfounded when realize they look exactly the same now as they did three years ago. If your goal is to grow, change, or improve, you simply must give your body more challenging obstacles to overcome!

Does this mean you should crank out reps to failure on every set of every movement? Nope. It means you need to have a system, and then have the patience to trust it for a matter of weeks, not just a workout or two.

Here are the two progressive overload techniques I use to help lifters of all levels progress safely and strategically to get stronger and bigger.

Technique 1 The No-Missed-Reps Model

In an ideal world, no one would ever miss a lift, and Keanu Reeves, by law, would never be able to make another movie. Unfortunately neither dream is likely to come true.

It's inevitable that most of us are going to miss a rep every once in a while, but in my opinion, a major difference between people who succeed and people who struggle in the weight room is that winners don't make a habit of missing reps consistently. Training to failure repeatedly will eventually fry your nervous system, leaving you exhausted and ripe for injury.

I'm not saying it's wrong to grind out a rep on occasion. There is something to be said for building mental toughness, but it's unnecessary to make it habitual. Quiz any elite powerlifter on how many times they miss a lift, and 95 percent of the time they'll say "zero," because they know it doesn't make them better.

Barbell Squat

If you're just starting to train, don't risk missing lifts just to hit an arbitrary number of reps or to "rep out" at the end of a workout. People love to argue about how many sets are "necessary" for hypertrophy, but I've found that more often than not, the quality of your training ends up being far more important to the results you earn than the quantity.

Still, plenty of people have trouble understanding that their only options aren't a) staying put forever, or b) cranking out reps to failure. This is the model I usually advocate for them to introduce progressive overload.

Say your main lift of the day is squats, and your plan is to perform 4 sets of 5 repetitions. It might look like this:

- Set 1: 10 warm-up reps with the bar (grooving technique)

- Set 2: 3 warm-up reps 3 reps at 95 pounds (still grooving technique)

- Set 3: 3 warm-up reps at 135 pounds

- Set 4: 1 warm-up rep at 155 pounds

- Sets 5-8: 5 working reps at 185 pounds

You nailed all the reps, with just a bit of grinding toward the end. Great! Now repeat the same format during the following week and you'll notice that it's even easier. If you're able power through all your working sets feeling like Batman, I've got good news for you: It's time to increase the weight, Bruce. Add 5-10 pounds and follow the same protocol; hit all reps for two consecutive weeks before adding any additional load.

This is pretty much guaranteed to work—to a point. Unfortunately, it's highly unlikely that you're going to take your squat from 185 to 500 pounds in a year this way. As you get stronger and more experienced in the gym, a sticking point will arise that can't be overcome by simply adding more weight. That's when it's time to change course.

Technique 2 The Two-Rep Window

When a more experienced lifter hits a weight ceiling with a step-based program, I like to give them what I call a "two-rep window." This progressive overload technique tweaks the number of reps rather than simply the load, and it's a good way to keep moving along in a classic 5x5 strength program.

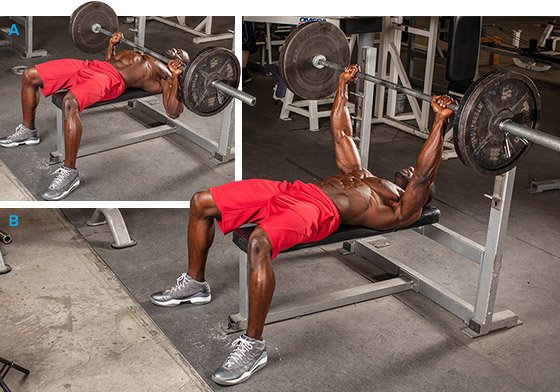

Barbell Bench Press

Say an exercise calls for 5 working reps. The two-rep window will allow for 3-5 reps. Here's how it would look for a hypothetical bench press workout:

Week 1 Bench press

- Set 1: 5 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 2: 5 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 3: 4 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 4: 4 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 5: 3 reps of 225 pounds

This progression cuts the set short at set 3, but still falls within the 2-rep window. Making this model work requires being able to shut out your ego and not make an attempt you're not sure you'll be able to pull off. All else being equal, I'd rather someone save a rep for next week rather than perform 1-2 questionable ones.

In this case, the trainee can make up the reps during the following week to keep progressive overload on track.

Week 2 Bench press

- Set 1: 5 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 2: 5 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 3: 5 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 4: 5 reps of 225 pounds

- Set 5: 4 reps of 225 pounds

The lifter performed three extra reps compared to the previous week. That may not sound like much, but think of it this way: That's 675 more pounds than their muscles were able to move just one week earlier.

Moving forward, the lifter would continue using the same weight until they complete all 5 working sets of 5 reps successfully. From there, they would increase the weight by 5-10 pounds and start the process over.

The Final Verdict

Determining how much weight you should use can be dwindled down to a two-word phrase: It depends. If you're willing to both push yourself and hold yourself accountable, these two techniques can help you travel a long way into the iron game. Give them a shot!