Sculpting a lean, muscular body is about more than just eating right and training hard. It requires advanced manipulation of anabolic and catabolic hormones throughout the day, ruthlessly battling and suppressing any substance that doesn't promote muscle-building—and especially when that hormone's name is cortisol.

Doesn't it?

Maybe not, or at least not to the degree some "experts" may lead you to believe. Due to the catabolic nature of cortisol, and the visceral desire of many bodybuilders to maintain a constant muscle-building state—all anabolic, all the time—much time has been spent trying to squash cortisol release. Workouts have been shortened and training intensities have been decreased in hope of keeping cortisol in check.

However, this view of cortisol and its short-term impacts on physique development is short-sighted—it doesn't take into consideration the difference between acute and chronic elevations in cortisol. Before you write me off as some heretic with a Ph.D., let's get deep into the role of the hormone cortisol in the muscle-building process.

What is cortisol?

Cortisol is a hormone released from your adrenal gland in response to physical—and mental—stress. Its primary functions are anti-stress and anti-inflammatory, meaning that it causes the body to suppress its immune response and stop responding to a problem or pain stimulus.

Owing to cortisone's immunoregulatory properties, pharmaceutical cortisol derivatives like prednisone are used to control strong allergic reactions, arthritis, and other inflammatory conditions. The dangers of chronically-elevated cortisol are obvious in the careful way these drugs are dosed, and by the short duration of treatments utilizing them.

In the short term, increases in cortisol are also associated with decreases in protein synthesis. The reason behind this is that one of cortisol's actions is to provide alternate fuels for the body when there is not enough glucose. This occurs during starvation or fasting, but also during intense exercise. Cortisol mediates muscle breakdown so that the amino acids in muscle tissue can be used to create sugar, via gluconeogenesis.

The human body cannot afford to waste energy while under duress, so it only makes sense that if cortisol stimulates the breakdown of muscle, it would also inhibit protein synthesis. Why build and break down something at the same time?

Cortisol and your workouts

Cortisol is generally talked about with great distain in bodybuilding circles, especially with respect to weight-training-induced cortisol increases. If left unchecked, cortisol levels can increase following exercise upward of 50 percent, which sounds like the recipe for a muscle meltdown.

However, while bodybuilders' personal universes may orbit around weight training sessions like the Earth does the sun, it's important to remember that our bodies do not have a similar dedication to the iron. The physiological processes taking place inside the human body at any given moment often have nothing to do with exercise or recovery—and this is true in regard to cortisol, as well.

In the 1998 paper "Stress-Related Cortisol Secretion in Men: Relationships with Abdominal Obesity and Endocrine, Metabolic, and Hemodynamic Abnormalities" (just some light bathroom reading), researchers from Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Sweden made several valuable contributions to our understanding of cortisol. First and foremost, single readings of a subject's cortisol levels "are not highly informative, because cortisol is secreted in a highly irregular manner."

Cortisol levels generally go up and down throughout the day, and an elevated level at any given point isn't indicative of a problem. On the contrary, cortisol levels that are variable, flexible, and responsive reflect a healthy endocrine system. If your body was to lose the ability to respond to stressors and appropriately regulate its cortisol levels, then that would be a problem.

A second point the Swedish study provides touches on something that many people get wrong in their quest for a six-pack. Cortisol is often billed as "the belly fat hormone," but the truth is that cortisol has its greatest impact on visceral fat, which is the fat which surrounds your organs—not the subcutaneous fat that covers your abs. If your abs are blurred due to an extra layer of fat, cortisol isn't the issue. You just need to get leaner.

The short-term impact of cortisol

In 2006, Stephen Bird published a series of papers that paint a good picture of the hormonal changes that occur as a result of weightlifting, and how different nutritional interventions impact these changes. When taken together, these papers provide a picture of the difference between short-term—e.g. during or after a training session—and long-term changes in hormones.

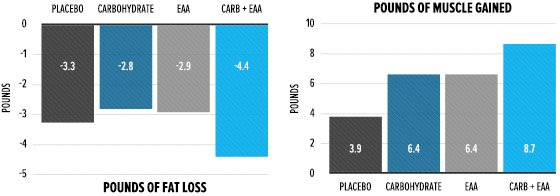

There were four groups of subjects in Bird's study, organized by what they were allowed to drink during their workouts: water, essential amino acids, carbohydrates, or essential amino acids plus carbohydrates. Over 12 weeks, all the groups lost approximately the same amount of body fat, and the group that had the most complete workout nutrition (EAA + Carbs) packed on the most muscle.

Now let's look at the acute changes that went with these big-picture changes. Researchers measured the amino acid 3-methyl-histidine in urine as a marker for muscle breakdown. As shown in the graph below, the group which drank only water (the placebo) had an increase in muscle breakdown 48 hours after its training session. There was no change for the groups that had essential amino acids or carbohydrates. The group that had the combination workout drink actually had a decrease in its 3-methyl-histidine levels after training.

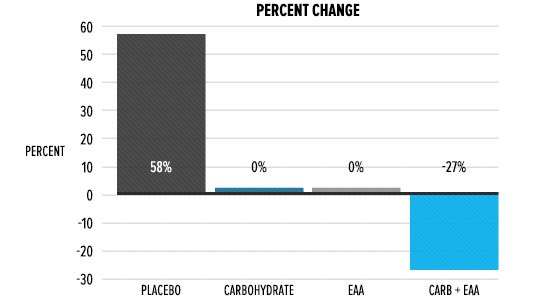

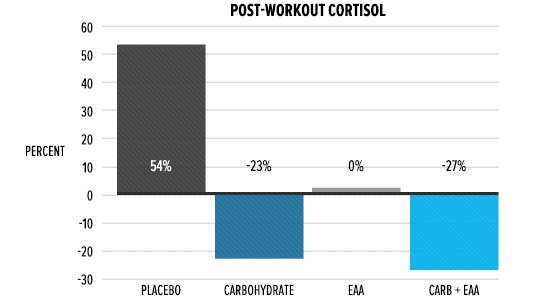

What happened with cortisol? As you can see below, cortisol levels 30 minutes following exercise were increased by more than 50 percent in the group which drank water, but unchanged in the EAA group. Cortisol was decreased in both groups which had carbohydrates as part of their workout nutrition.

Think back to when I was explaining gluconeogenesis, the process in the liver that creates glucose from non-sugar sources to provide energy to parts of the body that need it. The body doesn't need to generate its own sugar—a metabolically intensive process—when there is extra sugar from a sports drink floating around the blood stream. Thus, there was no increase in cortisol when carbs were present.

That short-term muscle loss and cortisol spike for the water-drinking group may seem significant, but don't forget that all the groups gained muscle over the course of the study. The group that just drank water added almost four pounds of muscle over 12 weeks!

Short-term cortisol spikes decrease over time

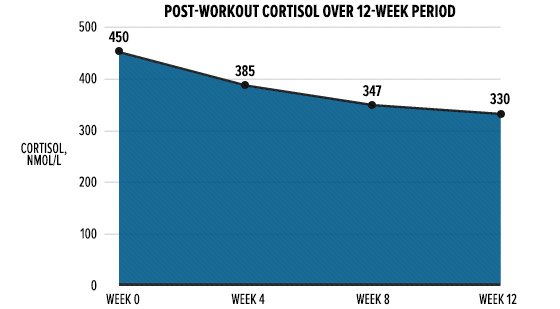

So the people with the highest catabolic response still gained muscle? How can this be? It seems simple, really: Their bodies adapted to the weight training stimulus over time and released less and less cortisol, even without any nutritional intervention. For the water-drinking group, post-exercise cortisol levels decreased 28 percent over the 12 weeks of the study.

Yes, it turns out that cortisol levels and acute muscle breakdown don't have a negative impact on muscle gains or fat loss over a 12-week period. If a recent study from McMaster's University is to be believed, the opposite might be true.

Researchers at McMaster's looked at the relationship between post-workout cortisol levels and changes in strength, lean body mass, and muscle fiber cross-sectional area. They found that after 12 weeks of resistance training, high post-workout cortisol levels were (albeit weakly) correlated with gains in lean body mass and changes in type II muscle fiber size.

This bears repeating: The people with higher cortisol levels were the ones more likely to gain more muscle over the course of the study. This the opposite of what cortisol-haters would have expected!

Moving forward

The data says that if you ever cut a workout short or lift with reduced intensity out of fear that your post-workout cortisol levels would soar, then you were probably misinformed. The McMaster study hinted that there may even be a correlation between acute cortisol elevations and long-term muscle growth.

You might wonder, "If acute elevations in cortisol reflect a good training session, then should I stop using nutritional protocols that reduce cortisol?" I would say, no, don't skip your workout nutrition. Protein and carbs taken before, during, and after a workout are still important for jumpstarting the recovery process, so you can come to your next training session bigger and stronger.

In these situations, elevated cortisol is simply a marker of a productive workout. And lest we forget, the group in the initial 12-week study that had aminos and carbs gained more than twice the muscle of those drinking only water.

A final concern: If we should basically ignore post-workout cortisol levels, does this does mean that we should just forget about cortisol altogether, and disregard any long-term changes in our levels?

Definitely not!

The long-term changes in cortisol and the decrease in cortisol flexibility should concern us. The systemic effects of this catabolic hormone need to be considered when looking at the big picture of our training, nutrition, and lifestyles in general. You shouldn't measure daily changes in cortisol flexibility, but you should still do your best to control it.

Adequate sleep, calories, and attention to recovery are the three biggest factors that we have control over on a daily basis. In addition to these things, supplements like rhodiola rosea have been suggested to aid in adaptation to stress and further guard against chronic cortisol elevation.

No matter how strong or fit you are, high cortisol levels induced by chronic stress can wreak havoc on your mental and physical well-being. They put you at increased risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease and exacerbate just about any other problem you might suffer from. Remember, however, to keep things in perspective and take the long view. Don't sweat the small stuff!

Additional Reading

- Liquid carbohydrate/essential amino acid ingestion during a short-term bout of resistance exercise suppresses myofibrillar protein degradation.

- Effects of liquid carbohydrate/essential amino acid ingestion on acute hormonal response during a single bout of resistance exercise in untrained men.

- Independent and combined effects of liquid carbohydrate/essential amino acid ingestion on hormonal and muscular adaptations following resistance training in untrained men.

- Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities.

- Associations of exercise-induced hormone profiles and gains in strength and hypertrophy in a large cohort after weight training.

Recommended For You

5 Ways To Grow More Muscle Day And Night!

If you've got your diet and training fundamentals down but are looking to maximize protein synthesis, try these five master-level nutritional strategies!

Citrulline Malate: The Fatigue Fighter!

No modern pre-workout or pump-boosting supplement is complete without citrulline. Here's why this amino acid is earning its way to the ergogenic hall of fame!