As a registered dietician, I'm often asked what the difference is between simple and complex carbohydrates. The short answer: not much. They're both carbohydrates that end up broken down into glucose, which is the major fuel source for your body. The long answer: Everything related to health, digestion, fullness, and nutrition separates the two.

The flexible dieting crusade has led many people to believe there's no difference between 25 grams of carbohydrates from a sweet potato or a sleeve of SweeTarts. As long as you're hitting your daily numbers, they argue, you're A-Okay!

In reality, the structure and nutrient content of a carbohydrate significantly affects how your body digests it, which influences blood-glucose and energy levels, as well as fullness. If you're constantly taking a numbers-based rather than a health-based approach to carbohydrates, you'll be riding the energy roller coaster all day long. This doesn't bode well for your long-term metabolic health or your attempts at weight loss.

The majority of the time, you're better off reaching for a complex rather than a simple carb.

1. Structure

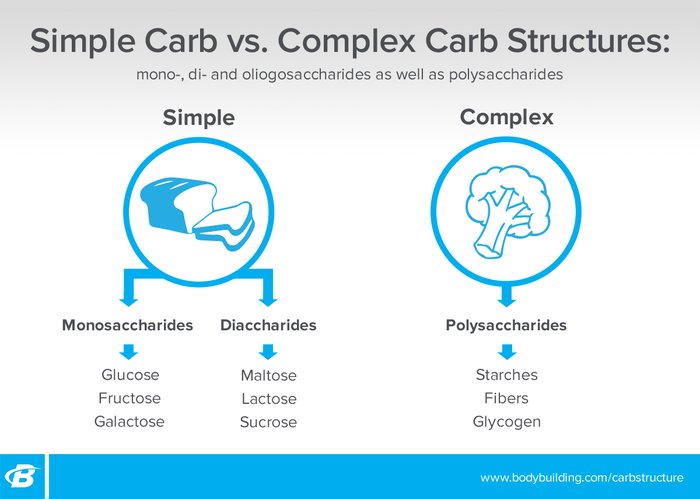

Simple carbohydrates are composed of a single sugar unit, or multiple units strung together (fewer than 20 units), whereas complex carbohydrates are composed of strands with at least 20 sugar units, and often more than 100. This structure means the body will break down and digest each differently.

2. Glycemic Index and Speed of Digestion

The glycemic index (GI) is a system that ranks carbohydrates (on a scale of 0-100) by how quickly glucose (the end product of carbohydrate breakdown) enters the blood. The higher the GI value, the quicker glucose enters the bloodstream after eating that food.

- Simple Carbohydrates: White potato, white bread, white rice, cookies, candies, fruit juice, sports drinks

- Complex Carbohydrates: Brown rice, oats, apples, oranges, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots

How fast glucose enters the blood has a big impact on your health, energy levels, and appetite.

3. Insulin and Blood Glucose Response

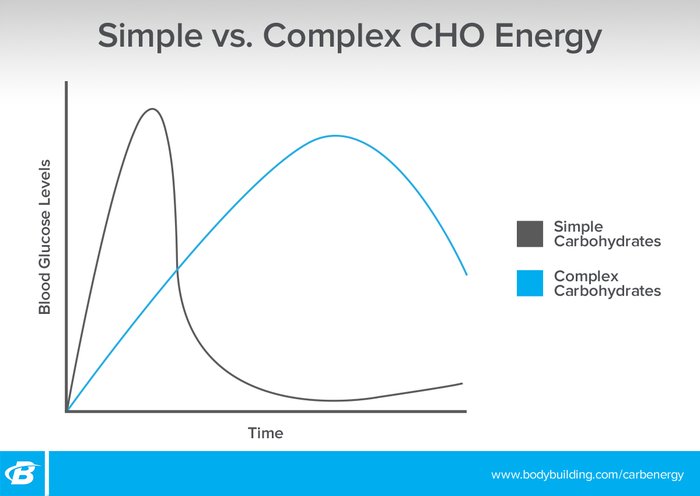

When glucose enters the bloodstream, your pancreas releases insulin to shuttle glucose away for storage in muscle or fat cells to maintain a normal blood glucose range. When glucose rapidly enters the blood—as is the case after eating a piece of candy or a cookie—a large amount of insulin is released in an effort to quickly shuttle glucose to its destination.

Over time, excessive production of insulin, known as hyperinsulinemia, taxes the pancreas and leads to insulin dysfunction, which is associated with impaired glucose tolerance and usually weight gain, too.[1] As a result of frequent insulin exposure, cells may become numb to the effect, a condition called insulin resistance. This results in elevated blood glucose levels. The presence of both conditions has an additive impact on the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes and several other metabolic abnormalities.[2-4]

Conversely, eating complex carbohydrates results in the slower release of glucose into the bloodstream, lower insulin release, and steadier blood glucose levels. This bodes well for long-term health.

4. Energy Levels

Consider the unintended consequences when you skip a meal, which might be a part of your weight-loss plan, or a result of your busy schedule. When you go a long period of time without food, blood glucose commonly dips below normal levels, which is referred to as hypoglycemia. Common symptoms include fatigue, lightheadedness, hunger, and an intense craving for sweets.

Eating simple carbohydrates when you've gone too long without food will cause a rapid rush of glucose into—and then out of—the blood, resulting in a dip in blood glucose levels. So choosing simple carbs over complex throughout the day can bring you up and down repeatedly, putting you on an energy roller coaster.

5. Fullness

Physical hunger is related to digestion and the volume of food in your stomach. The faster carbohydrates are digested and pushed through the stomach and into the intestines, the sooner you'll feel hungry again. The fast-digesting nature of simple carbohydrates isn't ideal for maintaining satiety.

A complex carbohydrate, on the other hand, takes longer to break down and is also typically in part composed of indigestible starch known as fiber. Fiber is technically a carb, but it doesn't really act like one. It's effect on slowing digestion allows more time for appetite-suppressing hormones to be released and fullness signals to be sent to the satiety center in your brain.

Fiber also adds bulk to meals, which takes up more space in your stomach.[5] The natural stretching that occurs as a result ultimately acts as a satiety signal. If you're in the midst of a dieting phase, make fiber your best friend!

Of course, portion sizes and the other nutrients included in the meal significantly affect fullness, but on their own, simple carbohydrates will leave you feeling hungry soon after.

6. Nutrient Content

It's common sense that candy, cookies, and cakes aren't very nutritious, but even grains touted as "healthy," such as rice, pasta, and bread, may be similarly nutrient-poor.

The whole grain can be stripped of the endosperm and bran, which are rich in nutrients, fiber, and healthy fats. This leaves a simple carbohydrate. By removing these two layers, the grain is no longer whole, and more than 15 vitamins and minerals are discarded, as well as satiety-boosting and digestion-extending fiber. Sure, a process known as "enrichment" adds back some nutrients, but not all—and definitely not fiber.

Left unprocessed, the whole grain is rich in nutrients and fiber, and it remains a complex carb. By making whole-grain options such as brown rice, oats, and whole-wheat bread a staple in your day, you'll reap the benefits of a nutrient-dense diet, which can improve health, energy, and immune function.

The Bottom Line

Should you avoid simple carbohydrates? Absolutely not; they do have their time and place, such as during and after training, as well as in moderation for special occasions. But if you're looking to optimize health, increase energy, and curtail hunger—which is key for dieting—you need to know the critical differences.

Choose fiber-rich, complex carbohydrates over the stripped-down, simple version most of the time, and you'll take better control of your weight, health, and energy.

References

- Li, C., Ford, E. S., Zhao, G., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). Prevalence of pre-diabetes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors and hyperinsulinemia among US adolescents National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Diabetes Care, 32(2), 342-347.

- Carey, D. G., Jenkins, A. B., Campbell, L. V., Freund, J., & Chisholm, D. J. (1996). Abdominal fat and insulin resistance in normal and overweight women: direct measurements reveal a strong relationship in subjects at both low and high risk of NIDDM. Diabetes, 45(5), 633-638.

- Martin, B. C., Warram, J. H., Krolewski, A. S., Soeldner, J. S., Kahn, C. R., & Bergman, R. N. (1992). Role of glucose and insulin resistance in development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: results of a 25-year follow-up study. The Lancet, 340(8825), 925-929.

- Shanik, M. H., Xu, Y., Škrha, J., Dankner, R., Zick, Y., & Roth, J. (2008). Insulin Resistance and Hyperinsulinemia Is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care, 31 (Supplement 2), S262-S268.

- Phillips, R. J., & Powley, T. L. (1996). Gastric volume rather than nutrient content inhibits food intake. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 271(3), R766-R769.