Football is a dangerous game of collisions, dynamic acceleration, and brutal twists and turns. One wrong step, abnormal twist, or botched landing, and a year of an athletic potential slumps to the turf.

New York Jets All-Pro cornerback Darrelle Revis is considered one of the greatest athletes in football. He isolates receivers so completely that quarterbacks are said to desert them on "Revis Island." But on September 21, 2012, as Revis sprinted to tackle a Miami Dolphin receiver, he momentarily adjusted his sprint and his knee buckled. Revis was carted off the field in the third quarter, his face in his hands, his season done after three games. The diagnosis, as it has been for several other players early in the season, was a tear in his anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

Approximately one in five NFL injuries occur in the knee, and the tears and ruptures in the ACL are the most common knee injury. The combination of speed, sudden stops, and physical obstacles on the football field creates a perfect environment for leg injuries—especially to the four ligaments in the knee.

However, big hits aren't always to blame. Approximately 80 percent of sports-related ACL tears are non-contact injuries—including the one that ended Revis' season. ACL injuries occur commonly among skiers, trail runners, soccer players, ladies jumping out of pickup trucks, and old dudes playing 500 with their nephews. No matter the setting, if fast-paced jumps and turns are involved, you're at risk. Injuries occur whenever a knee joint is required to bend backward, twist, or bend side-to-side.

The bad news is that in the case of both pros and joes, most—but not all—ACL injuries require surgery and lengthy rehab periods. But a torn ACL doesn't have to mean "game over" on your athletic life, as long as you do take your rehab seriously and do your homework. Let's get to know this much-feared injury.

The Crucial Ligament

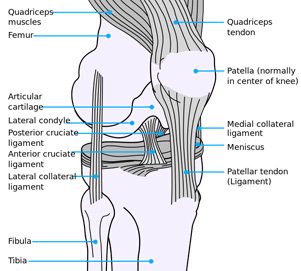

The knee is a vital joint to human activity. Without it, we can't even stand, let alone run and score touchdowns. But like every joint, the knee is more than just the meeting of two bones. It's a complex web of muscles, tendons (which connect muscles to bones) and ligaments (which connect bone to bone).

So where does the ACL fit in? Let's break it down:

- Anterior - Situated before or at the front; pertaining to the front plane of the body

- Cruciate - Shaped like a cross or an X

- Ligament - A band of fibrous tissue serving to connect bones and hold organs in place

The ACL originates from deep within the notch of the distal femur. Its proximal fibers fan out along the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle. In terms you may have heard before, the ACL connects the thigh bone to the shin bone. It also it stabilizes the knee during all types of movements.

When An Injury Occurs

You know you are injured when you hear and/or feel that blood-curdling "pop" in your knee.

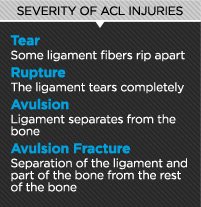

What just happened? The ligament may have either torn or snapped into shreds, leaving your leg bones floating nearly free in the knee joint. It may still be connected to one or both of your leg bones, but possibly not. You may have also injured the medial collateral ligament (MCL), which is on the inner side of your knee joint, or the outer lateral collateral ligament (LCL). A well-known 1995 study found that over 50 percent of ACL injuries involved MCL damage, while a third included LCL damage. If you damaged or tore the ACL, the MCL, and the meniscus (knee pads), you've experienced the "unhappy triad," or blown-out knee.

In the case of an ACL tear, you still may be able to walk on the knee, depending on the severity of the injury. But that doesn't mean you're out of the woods. Without a functioning ACL, your bones may rub against each other, causing bone bruising and other injuries. You're also at risk of damaging the menisci. According to one recent study, this can prove more detrimental to athletic durability than an isolated ACL injury.

When you injure your knee you should immediately implement R.I.C.E.: Rest, Ice, Compress, and Elevate. In the days following the injury, either visit your family physician or get an exam from an orthopedist. A simple stress test determines which tendon or ligament has been injured.

The Walking Dead

If you simply tore your ACL, then you might not need surgery—but then again, you still might. With luck, slight tears can heal with rehabilitation. The more severe the twist or bend, the more severe the injury, and the greater chance you tore multiple ligaments and will need longer rehab.

Once a ligament ruptures and blood flow is cut off, it cannot repair itself. If gone untreated, the nubs will erode and eventually disappear. The only way to begin the arduous process of ligament regeneration is for a surgeon to insert tendon tissue, often known as a "scaffold," into the knee. This allows blood to flow from one end to another, and your body slowly transforms the tendon into a ligament again.

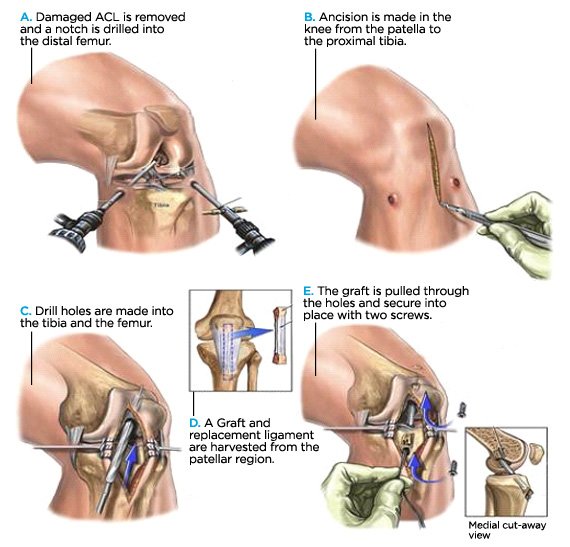

Reconstructive surgery connects the joint with either a tendon piece from your body (autograft) or from a cadaver (allograft). Both procedures begin with arthroscopic cleaning to remove remains of the old ACL, and also to determine the true state of the knee.

Autograft: The surgeon removes either the middle third of your own patellar tendon, which holds kneecap in place, or a doubled-over piece of your hamstring tendon. The segment is removed from its normal location and attached to both the femur and the tibia with dissolvable screws. Once attached, blood flows through the tendon and slowly begins the process to transform it into a ligament.

Allograft: The surgeon inserts a piece of tendon from a cadaver. The tissues are removed by outside companies which test the ligaments for diseases, radiate the tissue with charged ions, then freeze-dry them for storage.

There are benefits and risks to both methods. An autografted tendon is thought to heal and mature more quickly, but since the procedure requires another injury to the patient, recovery can be long and painful. There is also the possibility that your hamstring or patella will be weakened in the long-term.

On the other side, an allograft procedure entails less initial pain, because you are not taking tissue from another part of your own body. However, the dead tissue from the cadaver generally requires more time to mature and strengthen within your body. While you may feel better six months out with a cadaver tendon, it may be structurally less strong than an autograft, putting you at risk for re-injury when you overestimate your healing.

Ready For Rehab?

Your ACL rehab begins before you even have surgery. Physical therapists will begin by increasing your range of motion immediately, to help rebuild the strength in the damaged area. Sometimes, as in the case of Darrelle Revis, the patient may not even go under the knife for a matter of weeks.

No matter whether you choose an autograft or allograft, the muscle groups that balance the knee joint will be affected. Physical therapy and weightlifting are required to strengthen the affected muscle group. Without the resistance training, injuries to the kneecap, hamstring, meniscus, and the repaired ACL are a serious risk, especially if you return to vigorous activity too soon.

Post-surgery rehab can take five months to two years. The muscle groups surrounding your knee will lose tone and strength. It takes time, patience, and hard work to earn that tone back. Just 3-4 days after your operation, you begin the long road to recovery with mild exercises and weight lifting. Different doctors and physical therapists will favor different moves, but early on, all will have little-to-no impact on your knee. Normally, you'll begin with machines and then move to resistance bands and eventually free weights.

Here is a sample home exercise program for an ACL reconstruction, provided by the Idaho Sports Medicine Institute in Boise:

Work for full extension and full flexion (unless limited by meniscal repair) at least twice daily. Emphasize full extension, including hyperextension, equal to the other knee.

Medial, superior, and inferior glides and lateral tilt done with the quads relaxed.

Quad extensions, hamstring curls, calf raises, leg press, short squats, standing knee extensions (using tubing placed behind the knee), resisted plantar flexion, hip adductor/abductor, seated/standing quad sets with surgical tubing.

Standing broad jump, 2-legged jumps, 1-legged jumps, 180-degree jump spins, sideways jumps, box steps, box jumps (different angles, directions, heights), focus on proper hip, knee, and foot alignment.

With crutches, weight bear as tolerated, using a heel/toe gait and working for full extension of the knee. Crutches may be discontinued as soon as the patient has good muscle tone, motion and can walk without a limp. Try in front of a mirror, hold onto a counter for balance, or balance on the injured leg.

Your care provider will have his or own program for sports-related rehab, but you're likely to see a combination of short squats, extensions, presses, jumping, and step-ups, depending on your tolerance and if you had an autograft from your hamstring. Aerobically, get used to the machines: stationary bike, treadmill, and elliptical. You can swim in time, but avoid frog kicks or vigorous flutter kicks. For a while at least, be happy with just walking in the pool.

The Long-Term

Once you tear up your knee, the original makeup of your joint is gone. Welcome to cyborg life. Yes, you can heal and return to the mountain, the pitch, or the gridiron, but remember that you are now a science experiment, and there are side effects.

"The knee is never normal again," Moore says. "It may not ever bug you, bother you, but once you get an inury and a surgery, the knee is never the same."

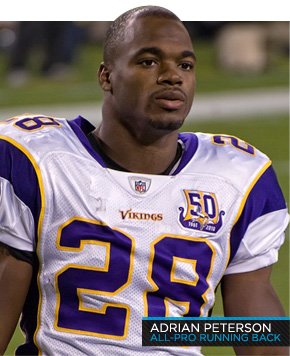

Amazingly, NFL players generally return from these injuries to play again, regardless of age and position. Sometimes, they even thrive. On December 24, 2011, Adrian Peterson of the Minnesota Vikings tore his ACL and his MCL. After reconstructive surgery and eight months of rehab, Peterson returned to the NFL for week one of the 2012 season to rush for 84 yards and two touchdowns, becoming the Vikings' all-time leading rusher.

Peterson, a gym beast, is a genetic anomaly. Results like his are not typical, even in the NFL. A study in the The American Journal of Sports Medicine in 2006 tracked NFL running backs and wide receivers who had sustained ACL injuries and found that while almost 80 percent returned to play, their on-field performance dropped by an average of 30 percent by a range of markers. So it should come as no surprise that for the rest of us mortals, long-term effects are likely after an ACL injury. For example, athlete or not, you're more likely than not to suffer from osteoarthritis in your knees after having suffered an ACL injury. In the shorter term, re-injuring the knee is a distinct risk, as is injuring the other knee through overcompensation or fear of injury.

The pain is inevitable. Rehab can take months or years, and the pain will be there through it all. Then one day, it will be almost or totally gone, but even then it's important to continue strength training to protect the knee. The hams and quads are your knees' bodyguards. Use them.

Accident Avoidance

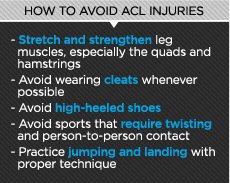

There are a number of things you can do to strengthen your body and your knee joint, so you your chances of tearing—or re-tearing—a ligament decrease.

First, learn how to jump and land. Technique is paramount in sports and can often trump natural athleticism. You may not be able to stop linebackers from twisting you up during a tackle, but by practicing how to jump and land, you can protect yourself from your own bad form.

When you jump (over a defender, a fence, or a mogul) keep your hips, knees and feet in alignment, so that when you land, they are still aligned. If you land with your feet at angles, your ligaments may rupture due to the compressive force of your body colliding with the ground. A player can jump-cut, land wrong, and his or her knee will buckle.

"We try to get people to where they are strong enough—and aware enough—that whenever they land, they land with their knees bent just a little, or [they] get strong enough to land with good alignment," says James Moore, and exercise physiologist at the Idaho Sports Medicine Institute, which treats the Boise State University football team and other collegiate, semi-pro, and amateur athletes. "Even with good strength, if you land incorrectly just once you can tear a ligament."

Moore also suggests that children and adults participate in multiple sports to develop muscle strength in areas that certain sports don't provide. Weightlifting is also vital to young athletes, many of whom try to play sports without training.

He points to a study the institute conducted way back in 1980. That year, they found 22 torn ACLs among high school girls participating in sports, while only two boys suffered the injury. The reason had less to do with gender than with physical fitness. Most of the girls had never done weight training, so their knees were not properly supported by muscle.

To develop that strength, implement both isolation (e.g., leg extension) and compound (e.g., squat) leg exercises to target the muscle groups in the quads, glutes, hamstrings, and calves. Moore says isolation exercises are particularly effective in helping guard against injuries that occur during the sudden slow-downs and stops of action sports.

"You need to develop the muscles to decelerate," he says. "The big emphasis for strength coaches is to do all the explosive lifts, and they don't do any isolation stuff anymore in the quads and hams. Develop quads with the knee straight, so when you land and come to a stop your knee bends. That's exactly what you do when do leg extensions."

The Future of ACL Treatment

Due to the intensive rehab and slow recovery demanded by conventional ACL treatments, athletes are often willing to travel around the world and spend plenty of cash on experimental procedures. Many of these promising techniques are not yet legal in the United States or have not been evaluated or approved by the FDA or the AMA.

Perhaps the best-known new technique in recent years involves injecting platelet-rich plasma (PRP), pulled from the athlete's own blood, into weakened areas. Hundreds of hospitals and thousands of independent doctors now offer this relatively inexpensive treatment worldwide. A recent review of controlled trials for PRP injections after ACL grafts found that the injections could speed graft maturation by 20-30 percent. This has great appeal for professional athletes like Chicago Bulls point guard Derrick Rose. He underwent PRP treatment in addition to having a patellar tendon transplant after suffering a brutal ACL tear in the 2011 NBA playoffs.

German doctor Peter Wehling has also received a lot of attention for a small change he made to the PRP protocol. He heats the patient's blood prior to spinning it, which he claims serves to further isolate healing and anti-inflammation agents. Athletes such as Kobe Bryant and Alex Rodriguez, and even the late Pope John Paul II, tried the therapy on their chronically bum knees.

A group of Italian doctors has added stem cell therapy into the mix, in the hopes of avoiding surgery altogether, as well as the complications that sometimes accompany patella or hamstring tendon harvesting. In a 2009 study, Dr. Alberto Gobbi and his colleagues at Orthopedic Arthroscopic Surgery International in Milan employed a unique procedure that involved suturing ACL tears in athletes and then creating small holes in the healthy remnants of the ACL to stimulate the creation of stem cells from bone marrow. Of the 26 athletes Gobbi and his colleagues performed the procedure on, 21 were able to return to their previous level of sports activity.

Novel techniques like stem cell therapy for ACL tears may be years from becoming widely available stateside. However, with billion-dollar sports leagues eagerly awaiting the latest new developments, these promising avenues of research have nowhere to go but forward. In time, they could be the key to shave months or years off of rehab and allowing patients to get back in the game sooner—and stronger.