When it comes to nutrition, false or misleading information seems to be everywhere. Start a conversation with a stranger—or even a loved one—and you'll hear how eating fat makes you fat. Too much protein, of course, will kill you deader than a ribeye. And yes, egg yolks are the devil.

The worst part? There are still plenty of nutrition "experts" making these claims, even in mainstream media where millions take their word as gospel! For this reason, it can be extremely difficult to determine what's accurate and what's nothing more than a bunch of gibberish.

Let's take a look at 10 common nutrition myths and uncover the truth!

Myth 1. Your Body Can't Utilize More Than 30 Grams Of Protein

People have claimed for years that the human body can only digest 30 grams of protein—or roughly 5 ounces of chicken—per meal. Anything over that will end up being stored as fat or just wasted. Can this really be true?

To understand how this seemingly arbitrary limit became the rule, it helps to go back to where it started. Years ago, it was shown that maximal muscle protein synthesis (MPS) occurred with roughly 20-30 grams of protein.[1] Increasing that amount to 40-plus grams of protein per meal was shown to be no more beneficial for protein synthesis. So does this mean your body stores the excess protein as fat? Not so fast!

Yes, excess amino acids can theoretically be converted into glucose—and ultimately be stored as fat in the body—but this is a long and costly process for the body. It's highly unlikely you'll get fat from excess protein. In fact, explorers who ate almost nothing but protein found themselves starving to death from a condition known as "rabbit starvation," not getting bigger! So let's go ahead and cross that one off the list.

It's highly unlikely you'll get fat from excess protein.

But does extra protein lead to bigger muscles? Muscle growth occurs when your body is in a positive nitrogen state, meaning MPS (think building of muscle) is greater than muscle protein breakdown (MPB). We know that MPS is maximized following the consumption of 20-30g of protein like whey. But what about MPB? Can muscle only apply that same 20-30 grams of protein in blunting MPB? Is there a corresponding MPB ceiling as well, or is that range closer to an “MPB floor?” That’s what researchers are trying to better understand.

A recent study found that consuming 70 grams of protein in one sitting significantly improved whole-body protein synthesis by drastically reducing muscle protein breakdown.[2] While we're still not sure about to what degree this might translate into bigger, stronger muscles, it does effectively debunk the notion that your body can't use anything more than 20 grams of protein at once.

The take-home lesson: If you want to maximize muscle growth and recovery, you need to both minimize muscle breakdown and increase protein synthesis. I'm not saying you need to eat 70 grams of protein at each meal, but your body can certainly utilize more than 30 grams of protein at one time!

Myth 2. A High-Protein Diet Increases Your Risk Of Osteoporosis

It's commonly said that a high-protein diet can contribute to osteoporosis, a loss in bone mineral density. The theory behind this states that a high-protein diet increases the acid in your body, causing calcium to get leached out of your bones to neutralize the acid. Sure, why not?

Fortunately, long-term studies examining the effects of protein intake and bone loss don't support these claims. In fact, in one nine-week study, in which carbohydrates were replaced with meat (increasing daily protein intake dramatically), hormones known to promote bone health, such as IGF-1, actually increased![3]

"This is an important 'myth' that needed to be busted," says Dr. Rob Wildman, chief science officer for Dymatize Nutrition. "This misinformation leads to many people unnecessarily limiting protein in their diet, especially older folks who clearly need to take in relatively more protein."

A review article published in 2001 also found no evidence that increased protein intake is harmful to your bones. If anything, the evidence points to a higher protein intake improving bone health.[4]

"This is an important 'myth' that needed to be busted," says Dr. Rob Wildman, chief science officer for Dymatize Nutrition. "This misinformation leads to many people unnecessarily limiting protein in their diet, especially older folks who clearly need to take in relatively more protein."

There are a handful of other studies showing that protein can improve bone mineral density, lower the risk of fractures, and increase IGF-1 and lean mass.[5-7] We can put this myth to rest.

Myth 3. A High-Protein Diet Puts Stress On Your Kidneys

Your kidneys are incredibly efficient at filtering unneeded substances from your body. And as far as we currently know, consuming a high-protein diet doesn't increase the strain on your kidneys. The kidneys are built to handle exactly this sort of stress!

To give you an example, one-fifth of the blood pumped by your heart gets filtered by your kidneys every minute or two. Adding a little extra protein may cause a slight increase in the workload, but it's really just a drop in the bucket compared to the total amount of work your kidneys already do.

That said, I do recommend increasing your water intake when you're consuming a higher quantity of protein, because your body produces more urine as a means to eliminate the byproducts of protein breakdown. Extra fluid is needed to replace what is lost via urine. But you should be drinking plenty of fluids anyway!

I'll tell you what does put a lot of unnecessary stress on your kidneys: alcohol. If you're looking to give your organs a break, start there!

Myth 4. Cooking Protein Changes Its Biological Value

Thank goodness this one doesn't have any truth to it. Otherwise, you'd see lifter after lifter downing raw burger patties post-workout. Thankfully, you can cook your protein and still reap all the benefits of it.

You can't cook the protein out of your meats; a well-done burger has just as much protein as a rare steak. Eating your meat raw will most likely just increase your risk of food poisoning.

You can't cook the protein out of your meats; a well-done burger has just as much protein as a rare steak.

More often, this notion comes up in regard to protein powders, which people say become "denatured" through cooking. This doesn't damage the protein though. Our bodies will still absorb the exact same amount of amino acids from the protein whether cooked or not.

Protein powders can even be baked. I'm always looking for ways to add a little extra protein into my diet, which has led to protein-packed oatmeal, muffins, and even pizza-crust recipes!

Myth 5. You Must Consume Protein Immediately After A Workout

Forget to consume 30 grams of protein immediately following your last set of curls? Well, you can say goodbye to your gains! It sounds like a joke, but I can't even begin to tell you how many times I've heard that thought expressed in the gym.

The so-called "anabolic window" is a period of time after your training when your body is most primed to accept nutrients—specifically carbs and protein—and deliver them to your muscles to help with repair and recovery. While it was once thought this window was only open for 30-60 minutes post-workout, we now know that it exists for a much longer period of time. In fact, it extends several hours after you finish your training session.

When it comes to packing on muscle mass, it appears protein timing isn't as important as once thought. What seems to be more crucial is the amount of protein you're consuming throughout the day. Regular doses of around 30 grams of protein are usually sufficient to support the growth and recovery of your muscles. Although post-workout nutrition is important—it's a great time to maximize muscle growth when protein synthesis is at its highest—your focus should be on the bigger daily picture, not just 30 minutes post-workout.

"Nutrient timing has evolved to be inclusive of the total 24-hour day and respecting timely, adequate protein—which would include the post-workout period," says Wildman. "Clearly, the hours immediately following a workout represent a time when MPS can be increased the most; however, the same loyalty should be shown to protein throughout the day as well"

If timing your shake immediately post-workout helps you do it consistently, then do it! But there's definitely no need to count the minutes.

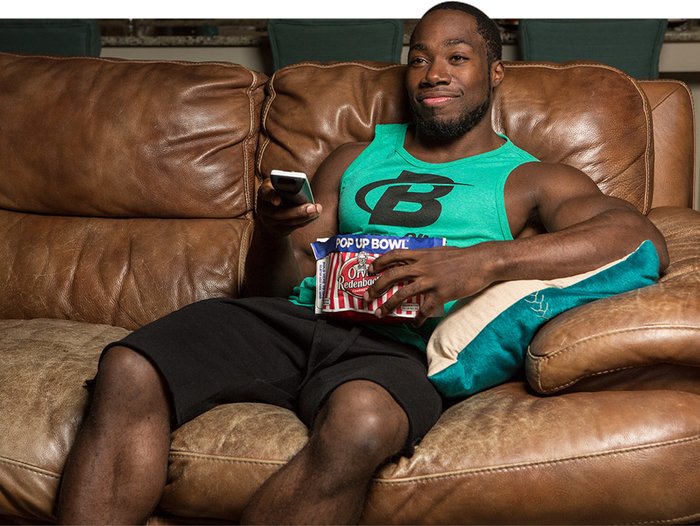

Myth 6. Carbs At Night Will Make You Fat

This sounds reasonable at first glance. Most of us are less active in the later hours of the day, and unless you're an avid sleepwalker, you're probably not getting much physical activity while you sleep. Therefore, any carbs you chow down on past 6 p.m. are likely to be stored as fat, because your metabolism slows down and insulin sensitivity is reduced.

But the reality is that your resting metabolic rate isn't much different when you sleep than it is during the day.[8,9] Exercising during the day can increase your sleeping metabolic rate significantly, however, leading to greater fat oxidation while you dream about 22-inch biceps.[10]

I'm not suggesting you save all your carbs for the evening, but if you're hungry and have a few more calories to go before finishing off your macros, don't fear the carb.

There's actually a case to be made that the opposite of this myth is true. A 2011 study examining the effects of carb timing found that participants who ate 80 percent of their total carbohydrate intake at night lost significantly more weight and body fat than the group who ate their carbs throughout the day.[11] Additionally, the group that feasted on carbs at night reported feeling less hunger.

I'm not suggesting you save all your carbs for the evening, but if you're hungry and have a few more calories to go before finishing off your macros, don't fear the carb. Coupled with a little protein, you'll not only go to bed with a happier stomach, but you'll help your muscles grow and recover faster.

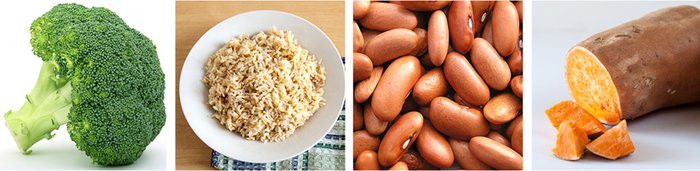

Myth 7. A Carb Is A Carb Is A Carb

While all carbs do have about 4 calories per gram, that's pretty much where the similarities end, at least in regard to how your body breaks them down and digests them.

For example, high-glycemic carbs are fast digesting, meaning they get broken down rather quickly by your body. This creates a rapid surge of glucose into your blood followed by a spike in insulin levels. Simple carbs can leave you feeling pretty sluggish about 45 minutes after you finish eating them, but they're great to have right after a workout, when your body needs to be refueled. Examples of these include baked goods, fruit juice, candy, most cereals, and anything made with white flour.

Low-glycemic carbs, on the other hand, digest much more slowly and allow for a steady release of glucose into your blood. These carbs should make up the bulk of your diet, as they will keep you fuller for a longer period of time, and often contain more vitamins and minerals compared to simple carbs. Examples of these include most veggies, brown rice, beans, and sweet potatoes.

Myth 8. Calories From Fiber Don't Count

Most of us are probably familiar by now with the term "net carbs." It was popularized by food companies during the Atkins craze to describe the total amount of carbs in a food after the quantity of fiber and sugar alcohols have been removed. The concept behind this is that not all carbs are equal in the way they affect the body (see Myth 5). Fiber and sugar alcohols are thought to have a minimal impact on blood sugar levels and are therefore subtracted from the total number of carbohydrates.

But there is one thing that sugar alcohols and fiber still contribute to: your overall calorie count! My guess is that if you're trying to minimize your carb intake, your goal is to lose weight. Unfortunately, counting net carbs and excluding the rest is going to give you an inaccurate total, and perhaps impact your results.

Most things in life don't come free, and this includes carbs. For best results, count all carbs toward your daily intake. And if you're going to consider anything "free," don't choose something that comes with a nutrition label. Make it a leafy green vegetable!

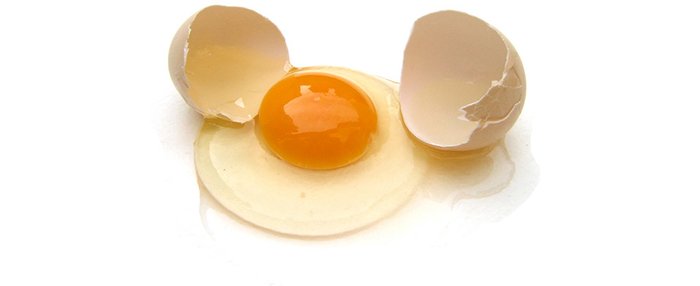

Myth 9. Egg Yolks Will Give You A Heart Attack

Those poor egg yolks have been getting a bum rap for decades. They've been targeted for increasing cholesterol levels, promoting heart disease, and wreaking havoc on your waistline.

Why all the hate? Years ago, researchers identified a correlation between dietary cholesterol from sources like egg yolks and elevated blood cholesterol levels. Elevated cholesterol levels can lead to hypertension and cardiovascular disease, thus the cultural ban on egg yolks and the start of the "egg white only" movement.

There's nothing wrong with eating egg whites; they're an excellent low-calorie source of protein. But forgoing the yolk means you're missing out on a ton of nutritional benefits. One whole egg contains around 7 grams of complete protein, and including the yolk makes it a better source of heart-healthy nutrients like omega-3s, B vitamins, and choline.

Although egg yolks contain about 185 milligrams of cholesterol, there are no controlled studies to date showing whole-egg consumption increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. In fact, one study conducted at the University of Connecticut found eggs yolks actually helped to increase levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, the "good" cholesterol).[12]

While observational studies may suggest a link between heart disease and egg consumption, it seems as though the real culprit in high cholesterol levels is the overconsumption of saturated fats and trans fats. Trans fats are often found in commercial baked goods and heavily processed fast foods.

As long as you haven't been advised to limit dietary cholesterol by your doctor for a specific reason, there's no reason to fear a couple of whole eggs a day. Shout it from the rooftops!

Myth 10. Eating Fat Makes You Fat

This one seems somewhat logical. The more fat we eat, the more fat we store on our body. It's the same word, right?

The reality is that fat is not the enemy—our overconsumption of calories in general is. Sure, eating a lot of fat-laden foods like fried foods, burgers, and deep-dish pizza can be one cause for your ever-expanding waistline, but so can chowing down on potatoes, Sour Patch Kids, and bagels, all of which have almost zero fat.

Try your best to prioritize monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats like olive oil, avocados, nuts, and fish.

If you're trying to lose weight, demonizing and avoiding fat is not the answer. Choosing the right fats can help keep you feeling full and satisfied for longer periods of time. Pair it with a lean protein source—also great for fighting off cravings—and you'll be less likely to find your hand in the cookie jar between meals. In fact, moderate amounts of fat in the diet have been shown to be more beneficial for weight loss than low-fat diets.[13,14]

Try your best to prioritize monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats like olive oil, avocados, nuts, and fish. Saturated fats, like those found in eggs and animal proteins aren't necessarily bad for you, but they don't offer up as many health benefits as unsaturated fats.

Here, as elsewhere on this list, moderation is key. Avoid thinking in absolutes and keep your BS meter up and running at all times!

References

- Witard, O. C., Jackman, S. R., Breen, L., Smith, K., Selby, A., & Tipton, K. D. (2014). Myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis rates subsequent to a meal in response to increasing doses of whey protein at rest and after resistance exercise. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 99(1), 86-95.

- Kim, I. Y., Schutzler, S., Schrader, A., Spencer, H. J., Azhar, G., Ferrando, A. A., & Wolfe, R. R. (2015). The anabolic response to a meal containing different amounts of protein is not limited by the maximal stimulation of protein synthesis in healthy young adults. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, ajpendo-00365.

- Dawson-Hughes, B., Harris, S. S., Rasmussen, H., Song, L., & Dallal, G. E. (2004). Effect of dietary protein supplements on calcium excretion in healthy older men and women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 89(3), 1169-1173.

- Kerstetter, J. E., Kenny, A. M., & Insogna, K. L. (2011). Dietary protein and skeletal health: a review of recent human research. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 22(1), 16-20.

- Bonjour, J. P. (2005). Dietary protein: an essential nutrient for bone health.Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 24 (sup6), 526S-536S.

- Munger, R. G., Cerhan, J. R., & Chiu, B. C. (1999). Prospective study of dietary protein intake and risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(1), 147-152.

- Rizzoli, R., & Bonjour, J. P. (2004). Dietary protein and bone health. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 19(4), 527-531.

- Seale JL, Conway JM. Relationship between overnight energy expenditure and BMR measured in a room-sized calorimeter. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999 Feb;53(2):107-11.

- Zhang, K., Sun, M., Werner, P., Kovera, A. J., Albu, J., Pi-Sunyer, F. X., & Boozer, C. N. (2002). Sleeping metabolic rate in relation to body mass index and body composition. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 26(3), 376-383.

- Mischler, I., Vermorel, M., Montaurier, C., Mounier, R., Pialoux, V., Péquignot, J. M., ... & Fellmann, N. (2003). Prolonged daytime exercise repeated over 4 days increases sleeping heart rate and metabolic rate. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, 28(4), 616-629.

- Sofer, S., Eliraz, A., Kaplan, S., Voet, H., Fink, G., Kima, T., & Madar, Z. (2011). Greater weight loss and hormonal changes after 6 months diet with carbohydrates eaten mostly at dinner. Obesity, 19(10), 2006-2014.

- Andersen, C. J., Blesso, C. N., Lee, J., Barona, J., Shah, D., Thomas, M. J., & Fernandez, M. L. (2013). Egg consumption modulates HDL lipid composition and increases the cholesterol-accepting capacity of serum in metabolic syndrome. Lipids, 48(6), 557-567.

- McManus, K., Antinoro, L., & Sacks, F. (2001). A randomized controlled trial of a moderate-fat, low-energy diet compared with a low fat, low-energy diet for weight loss in overweight adults. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 25(10), 1503-1511.

- Shai, I., Schwarzfuchs, D., Henkin, Y., Shahar, D. R., Witkow, S., Greenberg, I., ... & Stampfer, M. J. (2008). Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(3), 229-241.